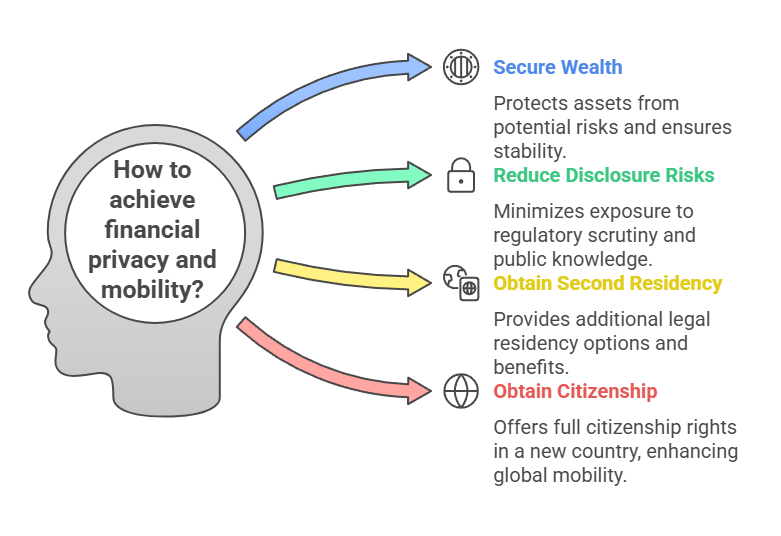

High-net-worth individuals (HNWIs), entrepreneurs, and investors often seek jurisdictions that offer investment migration programs, including citizenship by investment programs, combined with robust financial privacy protections. These select countries provide not only a pathway to a second residence or passport, but also strong safeguards like stringent banking secrecy laws, data protection regulations, minimal financial disclosure requirements, and limited information sharing with foreign authorities. This comparative analysis examines top-ranked investment migration destinations globally known for financial confidentiality, focusing on:

Banking secrecy laws – the strength and scope of client confidentiality.

Data protection regulations – especially as they pertain to financial data.

Local financial reporting requirements – what must (and need not) be reported by residents.

Tax transparency agreements – participation in frameworks like the OECD Common Reporting Standard (CRS) and U.S. FATCA.

Restrictions on information sharing – legal and practical limits on foreign access to financial data.

Privacy and Transparency Factors by Country

| Country | Banking Secrecy Laws | Data Protection | Local Financial Reporting | Tax Transparency (CRS/FATCA) | Info Sharing Restrictions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Switzerland | Legendary bank secrecy codified in 1934; illegal to divulge client info without consentPrivacy still strong, though softened for foreign tax matters | Federal Data Protection Act (updated 2023) similar to GDPR; strict bank client confidentiality by law. | Tax residents file annual returns incl. worldwide income/wealth (if not on lump-sum tax). No public asset disclosures; no exchange controls. | CRS: Implemented 2017, sharing since 2018 with 100+ countriesFATCA: Model 2 IGA; Swiss banks report U.S. accounts. | Only shares data per treaty/CRS. No “fishing” – partner must meet confidentiality standardsNon-partner countries (90+ nations) get no info |

| Singapore | Statutory bank secrecy (Banking Act s.47) prohibits disclosure of customer infoExceptions only by law (e.g. investigations). Culturally very discreet banking. | Personal Data Protection Act (2012) in force; banks must secure data and honor secrecy unless law compels. Strong financial data security protocols | Territorial tax – foreign income not taxed (if unremitted), so no need to report foreign assets. No personal wealth or capital gains taxes. | CRS: In force; first exchanges in 2018Built-in legal override of secrecy for CRS/FATCAFATCA: Model 1 IGA since 2015. | Shares info only with jurisdictions that ensure confidentialityOutlaws frivolous requestsNo routine foreign sharing outside CRS/FATCA and specific treaties. |

| UAE | Federal law (Art.120, 2018) mandates all customer banking data is confidentialBanks must obtain consent to release infoHistorically very secret banking culture. | Personal Data Protection Law (2021) – GDPR-like rights. Central Bank regs require minimal data collection and strict confidentialityFinancial free zones (DIFC/ADGM) have their own data laws, also robust. | No personal income tax → no tax returns at all for individuals. No requirement to report any foreign or local income. No wealth or inheritance tax. | CRS: Joined late; fully active by 2020/21, sending data as non-reciprocal (no domestic tax system)FATCA: Model 1 IGA, banks report U.S. accounts. | Disclosures to foreign authorities only via formal legal channels (MLAT or specific request) and with UAE approval. Banking Law penalizes unauthorized disclosure. CRS data only goes to partners with data security. |

| St. Kitts & Nevis | Strict confidentiality laws (e.g. Nevis Confidential Relationships Act) bar financial professionals from revealing client infoNevis notably keeps corporate ownership secret. | No comprehensive GDPR-style law yet; however, financial data protected by secrecy laws and industry regulation. Nevis trusts/LLCs enshrined with confidentiality. | No personal income tax, hence no personal financial filings. Companies under offshore regime file minimal info. CBI applicants’ identities kept confidential by policy | CRS: Implemented; first exchange in 2019Non-reciprocal (does not receive data). FATCA: Model 1 IGA signed 2015; reporting in effect | Very limited treaties. Foreign requests must go through local courts. No public registers for beneficial owners. Strong legal hurdles for information release to outsiders. |

| Malta | Banking Act and professional secrecy laws protect client info. As EU member, bank secrecy is tempered by EU directives, but unauthorized disclosure still illegal. Historically a high degree of bank confidentiality in private banking. | GDPR fully applicable (Malta was early adopter). Strict data protection oversight. Financial institutions follow EU-standard privacy and have reputational emphasis on confidentiality. | Residents taxed on domicile & remittance basis – foreign income not remitted is not taxed or reportedNo wealth tax. Ordinary residents file tax returns only on local/remitted income. | CRS: As EU state, automatic exchange since 2017. Malta exchanges info with all EU/OECD partners. FATCA: Yes, via EU-wide agreement. Malta’s due diligence for CBI ensures compliance with AEOI. | While Malta must share tax data under EU law, it fiercely guards personal data from public view. Names of CBI citizens are published in gazette (anonymously in a list), but no detailed financial data disclosed. Strong legal process needed for foreign info requests. |

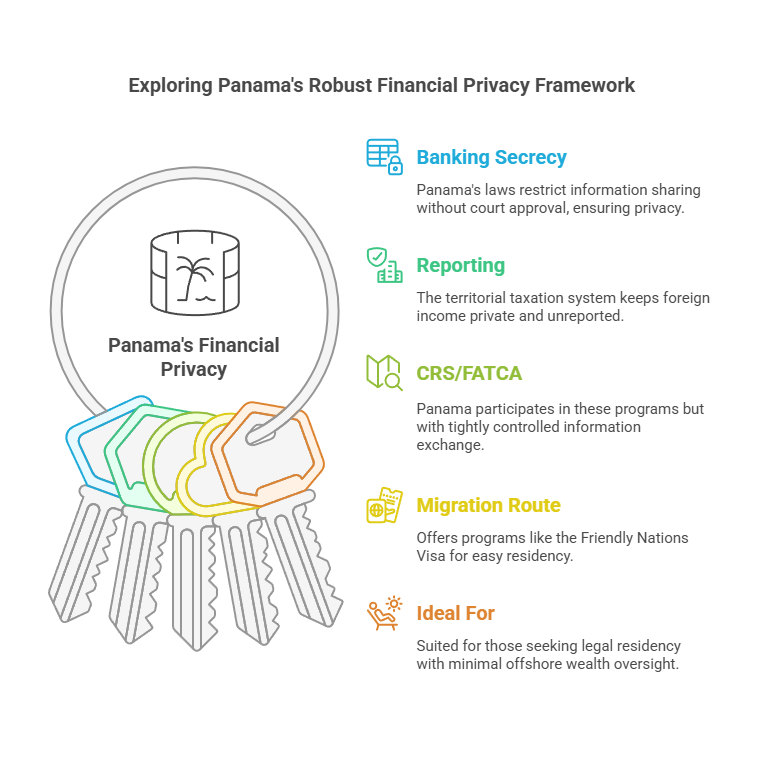

| Panama | Longstanding bank secrecy tradition (Law 9 of 1998); banks cannot give client info to third parties without consent or Panama court order. Panama was once synonymous with anonymous banking (e.g. famous “Panama Papers” banks). | Data Protection Law 81 of 2019 in force, regulating use of personal data with consent and securityBanking regulator enforces client confidentiality. Lawyers and registered agents bound by secrecy laws for companies/trusts. | Territorial taxation – foreign income not taxed, no requirement to declare foreign assets. No personal income tax if no local source income. No capital gains tax on offshore gains. Minimal financial reporting for offshore entities. | CRS: After initial hold-out, implemented by 2018; first exchange 2018Complied to avoid blacklistFATCA: Model 1 IGA, full FATCA compliance by banks. | Still among higher secrecy scores; only provides info under duress of agreements. Local law requires evidence of wrongdoing for info handover. Panama will suspend exchange if counterpart doesn’t protect data. Very reluctant to assist foreign fishing expeditions (improved post-Panama Papers, but remains cautious). |

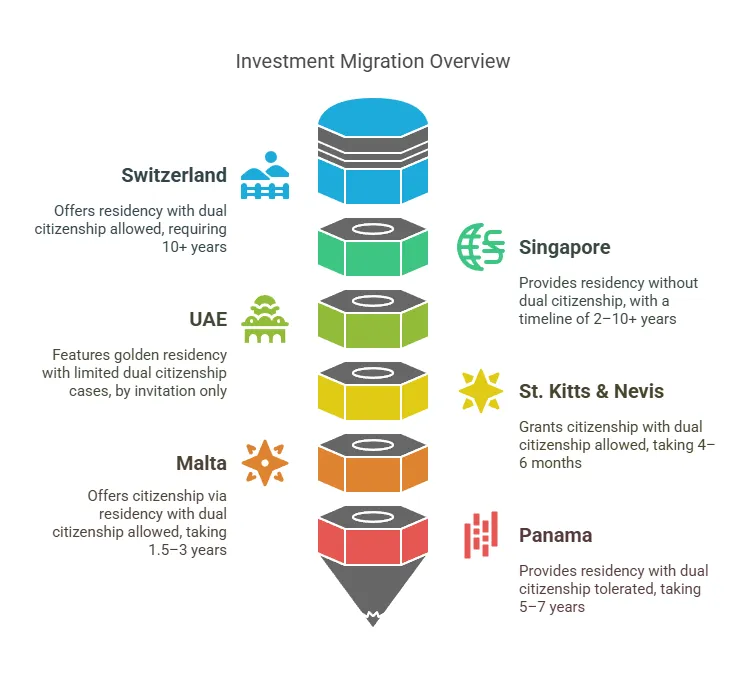

Investment Migration Programs and Citizenship Policies

| Country | Program Type | Investment Requirements (USD) | Processing Time | Residency/Naturalization | Dual Citizenship |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Switzerland | Residency (Investment via lump-sum tax or business) | Annual tax payment ≈ $275k–$1M (CHF 250k+ per year); alternatively substantial business investment creating jobs. In addition to the lump-sum tax, some cantons may also accept a substantial bank deposit as part of the investment criteria. | ~3–6 months for initial residence permit (varies by canton after tax agreement). | Eligible for citizenship after 10 years residency (strict integration tests) No expedited citizenship by investment – must fulfill ordinary naturalization. | Allowed. Switzerland permits multiple citizenships without restriction (No need to renounce original citizenship.) |

| Singapore | Residency (Permanent Residence via Global Investor Programme) | $1.8M (S$2.5M) investment in a new or existing business or approved fund Must have entrepreneurial track record. | ~6–12 months for PR approval (once investment and due diligence completed) | Can apply for citizenship after 2+ years as PR, but typically requires longer and deep ties. No guarantee; many remain PR indefinitely. | Not allowed for citizens. Singapore mandates renunciation of prior citizenship upon naturalization Dual citizenship is strictly prohibited beyond age 21 (PR holders keep original citizenship.) |

| UAE | Residency (Golden Visa – long term residence) | $545k (AED 2M) in real estate OR AED 2M in a company/investment fund Lower amounts for 5-year visa earlier, now largely AED 2M for 10-year. The UAE’s investor visa allows foreign nationals to obtain residency by making significant investments in real estate or business ventures. | ~1–3 months for Golden Visa approval after investment. Quick track; visas issued in a few weeks to a couple of months. | Golden Visa is a 10-year renewable residency. Citizenship only via nomination by rulers (exceptional cases). No timeframe to citizenship; generally not available through normal application. | Allowed in special cases. Historically banned, but since 2021 dual citizenship is permitted if one is granted UAE citizenship as an honor (For the vast majority just holding residency, they retain their original nationality by default.) |

| St. Kitts & Nevis | Citizenship by Investment (direct passport) | Donation: $250,000 to state fund (single applicant)\ Real Estate: $325,000 (approved property share) or $600k private home, held ≥5 years. \ + Due diligence & fees (~$7–10k). (Lower promotional rates occurred in past but $250k is current minimum.) The St. Kitts & Nevis citizenship program requires a significant financial contribution to the government or investment in real estate. | ~4–6 months for full citizenship and passport Accelerated 60-day process available at higher fee. | Immediate citizenship is granted; no prior residency required. Passport issued upon approval. (Optional: one can later establish residency in SKN, but not needed for the citizenship itself.) | Allowed. Dual citizenship is recognized without restrictions Investors keep existing nationality and St. Kitts does not report new citizenship to other countries. |

| Malta | Citizenship by Investment (naturalization after residency) | Contribution: €600k ($660k) for 36-month route or €750k ($825k) for 12-month expedited\ Real Estate: purchase €700k or rent €16k/yr (5-year commitment)\ Donation: €10k to charity \ + Due diligence fees ~€15k main applicant Total ~$900k–$1M all-in for one applicant. Malta’s citizenship programs offer a range of benefits, including enhanced global mobility and political participation. | *12 or 36 months residency* (choice determines contribution level), plus ~6-8 months processing citizenship Fast track ~18 months total, standard ~3 years. | Citizenship granted after 1–3 years of residency (per above). Applicants first get a residence card, then after the chosen residency period and final approval, receive citizenship. No physical stay minimum, but integration steps and Oath in Malta required | Allowed. Malta allows/recognizes dual citizenship. New citizens need not renounce other passports. (Many Americans, for example, hold Maltese citizenship alongside US.) |

| Panama | Residency by Investment (permanent residence, with path to citizenship) | Friendly Nations Visa: from ~$200,000 (e.g. real estate purchase) for permanent residence in 2 steps. \ Qualified Investor: $300,000 investment (real estate, or $500k securities, or $750k deposit) for immediate PR. \ Reforestation Visa: $100k in forestry + land (PR after 5 years). | Friendly Nations: ~3–6 months for temporary residency, then after 2 years, permanent residency. Qualified Investor: as fast as 30 days approval for PR. | Citizenship after 5 years of legal residency (3 years for some nationals). In practice 5+ years and Spanish language test. Many just keep PR which is indefinite. | Allowed (effectively). While Panama formally asks naturalizing citizens to renounce other citizenship, this renunciation is not enforced with foreign governments De facto dual citizenship is tolerated – many Panamanian citizens hold dual (the constitution’s ban is not applied if second citizenship acquired later). |

| Cyprus | Residency by Investment (permanent residence, with path to citizenship) | Real Estate: €300,000 (plus VAT) in residential property\ Business: €300,000 in Cypriot company (min. 5 employees)\ Investment Fund: €300,000 in Cypriot investment fund\ Combination: €300,000 in any of the above. Cyprus’s investment regulations also accept bank deposits as a reliable investment option for residency schemes. | ~2 months for permanent residence approval (PRP) Fast track; PRP issued in a few weeks to a couple of months. | Permanent residence granted immediately; citizenship after 7 years of legal residency (5 years in special cases). | Allowed. Cyprus allows/recognizes dual citizenship. New citizens need not renounce other passports. (Many Americans, for example, hold Cypriot citizenship alongside US.) |

| Australia | Residency by Investment (permanent residence, with path to citizenship) | Investor Stream: AUD 1.5M (USD 1.1M) in Australian state/territory bonds\ Significant Investor: AUD 5M (USD 3.7M) in complying investments\ Premium Investor: AUD 15M (USD 11M) in complying investments. Australia’s investment programs allow individuals to obtain permanent residency by investing in local assets or businesses. | ~12–24 months for initial visa approval (varies by stream) Fast track for Premium Investor; others take longer. | Permanent residence granted after 4 years of temporary residence (varies by stream). Citizenship after 4 years of legal residency (1 year as PR). | Allowed. Australia allows/recognizes dual citizenship. New citizens need not renounce other passports. (Many Americans, for example, hold Australian citizenship alongside US.) |

| Caribbean Countries | Citizenship by Investment (direct passport) | Donation: $100,000–$150,000 to state fund (single applicant)\ Real Estate: $200,000–$400,000 (approved property share) or $400k+ private home, held ≥5 years. \ + Due diligence & fees (~$7–10k). (Varies by country; some offer lower promotional rates.) In many Caribbean countries, obtaining citizenship can be achieved through financial contributions to the government or real estate investments. | ~3–6 months for full citizenship and passport Accelerated 60-day process available at higher fee. | Immediate citizenship is granted; no prior residency required. Passport issued upon approval. (Optional: one can later establish residency in the country, but not needed for the citizenship itself.) | Allowed. Dual citizenship is recognized without restrictions Investors keep existing nationality and Caribbean countries do not report new citizenship to other countries. |

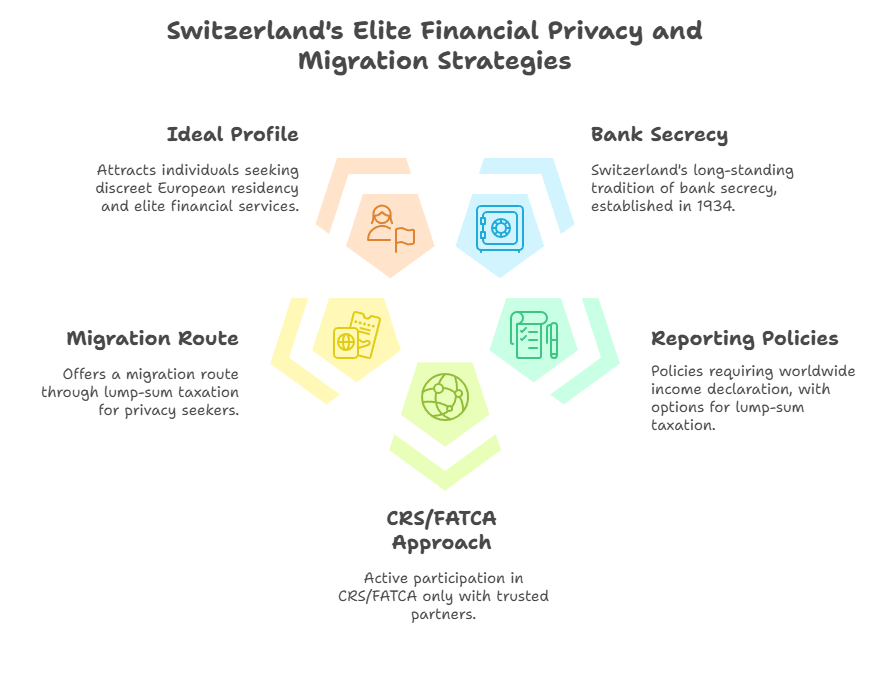

Switzerland

Banking Secrecy & Financial Confidentiality: Switzerland has long been synonymous with private banking. Swiss law codified banking secrecy in 1934, making it a criminal offense for bankers to divulge client information without authorization. Even today, Swiss bankers cannot legally disclose client details absent clear evidence of serious wrongdoing (e.g. tax fraud or money laundering) or an official legal request. This affords clients a high degree of anonymity and privacy in practice. Indeed, despite recent international transparency efforts, Switzerland remains one of the world’s most secretive financial centers – ranked the third-most secretive jurisdiction globally (after only the U.S. and Cayman Islands) according to the Tax Justice Network. Swiss bank-client confidentiality is comparable to attorney-client privilege and is zealously protected in domestic law. However, Switzerland has adjusted its secrecy stance under external pressure: it now cooperates with tax information exchanges while still shielding data from any disclosure that lacks a legal basis.

Data Protection: In addition to banking-specific secrecy, Switzerland enforces strict personal data protection. The Swiss Federal Act on Data Protection (FADP), recently updated (effective 2023), closely aligns with EU standards to safeguard personal information. Financial institutions must protect customer data against unauthorized access, and any processing of personal financial data is tightly regulated. Even when complying with foreign information requests, Swiss authorities ensure that confidentiality is maintained and only legally required data is shared.

Financial Reporting Requirements: For residents of Switzerland, personal financial reporting obligations are relatively contained. Switzerland does not impose any general requirement to file public financial statements or registers of assets. Tax residents do file an annual tax return that includes worldwide income and assets for tax assessment purposes (Switzerland levies taxes on worldwide income and has cantonal wealth taxes). However, under the popular lump-sum taxation regime available to wealthy foreign residents, one can pay a flat tax based on living expenses instead of declaring worldwide income. This means many investor migrants need not disclose detailed foreign financials locally as long as the agreed tax is paid. Aside from tax filings, there are no currency controls or routine asset-reporting mandates on individuals. Swiss law actually prohibits authorities from fishing into personal bank accounts without due cause. Thus, HNWIs in Switzerland enjoy a high level of financial confidentiality vis-à-vis the local government as well.

Tax Transparency (CRS & FATCA): While historically a holdout, Switzerland has joined global transparency initiatives in recent years. It signed onto the OECD’s Automatic Exchange of Information and implemented the CRS standard in 2017, with the first exchanges of account data occurring in 2018. Now, Swiss banks automatically report foreign clients’ account information to the Swiss tax authority, which forwards it to the client’s home country tax authority under CRS agreements. As of 2022, Switzerland exchanges financial account data with over 100 jurisdictions. However, importantly, Switzerland only shares data with partner countries that meet strict confidentiality and data security criteria, and over 90 countries (often less-developed) still do not receive any information from Switzerland. In those cases, Swiss bank secrecy remains effectively intact, allowing assets from those jurisdictions to stay hidden. Switzerland also entered a bilateral agreement with the U.S. under FATCA – Swiss financial institutions report U.S.-owned accounts either directly or via Swiss authorities to the IRS. These moves have tempered the absolute secrecy of the past, but Switzerland still limits information sharing to what treaties and laws explicitly require. No information is handed over to foreign governments unless pursuant to a valid agreement or legal process, and “fishing expeditions” are not permitted.

Restrictions on Information Sharing: Swiss law maintains robust barriers against unwarranted foreign intrusion. Any request for account-holder data must follow formal treaty channels (such as a Tax Information Exchange Agreement or mutual legal assistance in a criminal matter) and meet Swiss legal standards. Even under CRS, Switzerland insisted on reciprocity and confidentiality safeguards – it will suspend data exchange with any partner that breaches data security. Domestically, Article 47 of the Swiss Banking Act still ensures that unauthorized disclosure of client information by bank staff is punishable, reinforcing a culture of discretion. In summary, Switzerland’s framework strikes a balance between international transparency commitments and preserving client privacy. As one analyst noted, “banking secrecy is not dead” in Switzerland; the country continues to help foreign elites keep assets confidential, especially vis-à-vis countries not fully integrated into transparency accords.

Residency by Investment – Pathway: Switzerland does not offer direct citizenship by investment, but it has an attractive residence-by-investment (RBI) route via its lump-sum taxation program (also known as forfait or Swiss Residence Program). Wealthy foreign nationals who agree to pay a substantial annual tax can obtain a renewable residence permit without engaging in local employment. The minimum annual tax is typically CHF 250,000 (approximately USD 275,000) but can be higher depending on canton and individual circumstances. In practice, some cantons require a lump-sum tax of CHF 400,000 or more for very wealthy applicants. Alternatively, an investor can qualify by establishing a significant business that creates jobs in Switzerland (subject to cantonal approval), but the lump-sum tax route is more common for pure investors. Processing times for the residence permit vary by canton but generally take a few months once the tax agreement is approved. Applicants must be first-time residents in Switzerland (not having been tax resident in the prior 10 years) and financially independent. Under this scheme, the individual pays the fixed tax annually instead of normal income/wealth taxes, and in return gains a Swiss residence permit (typically a Canton-specific B permit initially).

Naturalization Timeline: Swiss residency can lead to citizenship, but only after a long-term commitment. Ordinary naturalization in Switzerland requires at least 10 years of lawful residence (recently reduced from 12 years), including at least 3 of the last 5 years before applying. Time spent in the country between ages 8–18 counts double (up to 4 extra years credit), and the applicant must hold a permanent residence (C permit) and demonstrate integration (language proficiency, etc.). In practice, investor residents often pursue citizenship after 10+ years if they have made Switzerland their primary home. The process is rigorous – taking 1–3 years and requiring federal, cantonal, and communal approval. There is no expedited “golden passport” in Switzerland; the RBI program grants residence rights, and citizenship comes only through the standard naturalization route over time.

Dual Citizenship: Switzerland allows dual citizenship without restriction. Since 1992, Swiss law permits multiple nationalities, so naturalizing as Swiss does not require renouncing previous citizenship. Many investor migrants maintain their original citizenship while enjoying Swiss citizenship once naturalized. During the residence period, one’s original citizenship is irrelevant to Swiss authorities (aside from visa entry formalities), and upon naturalization Switzerland imposes no requirement to relinquish other passports. This liberal dual citizenship policy adds to Switzerland’s appeal, as HNWIs can gain a Swiss passport (with its high global mobility) while retaining their home citizenship and any other citizenships.

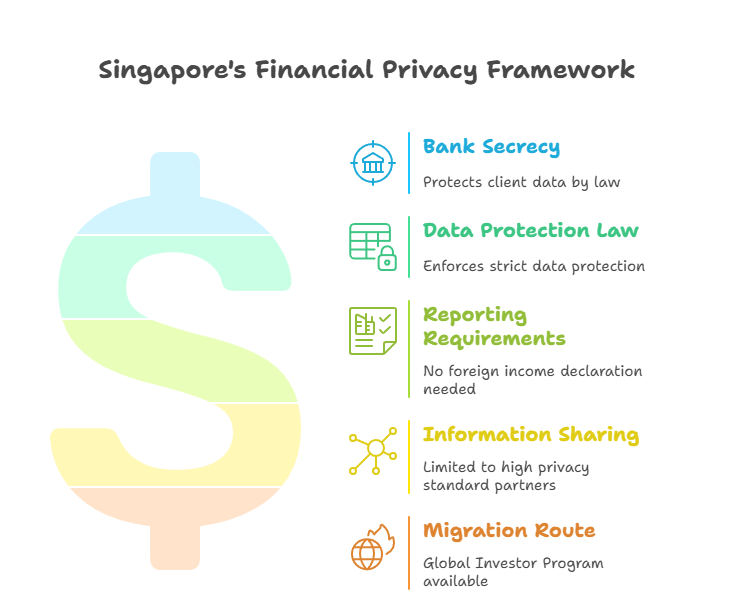

Singapore

Banking Secrecy: Singapore is another global financial hub renowned for strict bank-client confidentiality. Under Section 47 of Singapore’s Banking Act, banks and their officers are legally prohibited from disclosing any customer information to unauthorized parties except under tightly defined exceptions. This statutory banking secrecy covers all forms of account details and transactions. A breach of these confidentiality provisions by a bank employee can result in criminal penalties. In essence, Singapore’s banks provide a baseline of Swiss-like secrecy, ensuring that client financial data remains private by default. Banks may even offer higher-than-required confidentiality contractually, but the law guarantees a “basic level of confidentiality to all customers”. In practice, unless an exception applies (such as a court order or statutory requirement), banks in Singapore will not release client financial information to third parties, including foreign governments or private litigants. This makes Singapore a favored jurisdiction for those seeking discreet banking services in Asia.

Data Protection: Augmenting its banking secrecy, Singapore has a robust general data protection regime. The Personal Data Protection Act (PDPA) imposes strict rules on the collection, use, and disclosure of personal data, including financial information. Organizations must obtain consent to use personal data and ensure appropriate security measures. Additionally, Singapore has specific laws to protect banking and credit data – banks are required to treat customer data as confidential and secure. Under the PDPA and Banking Act, financial data can only be disclosed if an exception under the law is met (for example, disclosures to regulators, or for investigations). Notably, Singapore amended its laws to align with international tax cooperation: the Income Tax Act overrides banking secrecy and privacy laws for the purpose of complying with CRS and FATCA reporting. Even so, strict conditions apply to how such data is handled, and exchanged information is protected by confidentiality provisions on the receiving side. Overall, Singapore’s legal framework ensures that personal financial data is well shielded from public view, and even when shared for tax purposes, it is done under secure protocols.

Financial Reporting Requirements: For individual residents, Singapore imposes relatively light financial reporting obligations. Singapore operates a territorial tax system – generally only income sourced in Singapore (or remitted into Singapore) is taxable. Foreign investment income earned by a resident abroad can typically be kept out of Singapore tax scope if not remitted. As a result, residents are not required to report their worldwide assets or foreign bank accounts to Singapore authorities. There are no wealth taxes, no capital gains taxes, and no requirement for individuals to file annual net worth statements. Only taxable Singapore-sourced income (or foreign income remitted in certain cases) must be declared on an annual tax return. If a Singapore resident’s income is entirely overseas and not remitted, they may legitimately pay zero tax and not have to detail those finances locally. Moreover, Singapore has no exchange controls or currency restrictions on moving funds, and no mandated public disclosure of beneficial owners of private assets (aside from corporate entities’ registers, which are not public for most trusts or bank accounts). In summary, HNWIs living in Singapore can keep their offshore financial affairs private – they do not need to report foreign bank accounts, trusts, or income streams to the Singapore government as long as those funds remain offshore. This limited scope of reporting enhances financial confidentiality for those using Singapore as a base while maintaining wealth internationally.

Tax Transparency (CRS & FATCA): Singapore has committed to international tax transparency standards but with carefully managed execution. It signed a Model 1 FATCA intergovernmental agreement with the U.S., in effect since 2015, meaning Singapore-based financial institutions report U.S.-owned accounts to the local authority (IRAS) for onward transmission to the IRS. More broadly, Singapore is a participant in the OECD CRS, having enacted regulations to collect and exchange non-residents’ account information on a reciprocal basis. Singapore’s first CRS exchanges occurred in 2018, aligning with the timetable of over 100 jurisdictions implementing the Common Reporting Standard. To implement CRS, Singapore amended its laws to carve out exceptions to banking secrecy and data privacy, explicitly allowing banks to disclose account information to IRAS for CRS purposes despite any conflicting secrecy laws. However, there are built-in safeguards: Singapore will only exchange information with partner countries that ensure confidentiality and proper use of the data. “Fishing expeditions” are expressly disallowed. In essence, while Singapore complies with CRS and FATCA, it does so in a controlled manner – data is shared only under strict agreements and with jurisdictions that protect the data. Singapore itself does not publicly release names of new economic citizens or any financial info; all exchanges happen government-to-government. Domestically, Singaporean authorities do not pry into accounts without cause, so privacy remains intact for lawful account holders. It’s worth noting that Singapore was earlier perceived as a secrecy haven, but since 2016 it has actively avoided being labeled a tax haven by adhering to these global standards (albeit on its own terms).

Restrictions on Information Sharing: Outside of CRS/FATCA obligations, Singapore rarely shares financial information with foreign governments unless legally compelled. It has a network of Avoidance of Double Taxation Agreements (DTAs) and a few Tax Information Exchange Agreements, under which specific requests can be made for information in cases of tax investigations. Such requests must be detailed and cannot be speculative. Singapore will reject requests that lack sufficient basis or violate confidentiality rules. For criminal matters, Singapore cooperates via Mutual Legal Assistance treaties but again requires dual criminality and judicial oversight. The government has a reputation for rigorously upholding the rule of law – a bureaucrat or foreign agency cannot simply “browse” a person’s bank accounts in Singapore. As the Ministry of Finance highlighted, only jurisdictions with strong data safeguards get information, and if any breach occurs, Singapore can suspend data exchange. This measured approach means that investors’ financial affairs in Singapore are protected from arbitrary foreign scrutiny. In summary, Singapore balances compliance with international norms and protecting individual privacy. It remains a place where wealthy individuals can conduct banking and investment activities with a sense of security that their financial details will not be exposed without due cause.

Residency by Investment – Pathway: Singapore offers an exclusive residency-by-investment scheme called the Global Investor Programme (GIP). This program grants qualifying investors and entrepreneurs Permanent Resident (PR) status in Singapore. To qualify, an applicant generally must invest at least S$2.5 million (approximately USD $1.8 million) in one of the approved options: either in a new or existing business in Singapore or in an authorized fund that invests in Singapore-based companies. Applicants should also have a successful entrepreneurial background or track record (e.g. running a profitable company) to be approved. The GIP is highly selective – beyond the monetary investment, authorities evaluate the applicant’s business credentials and potential contribution to Singapore’s economy. If approved, the investor and immediate family obtain Singapore PR, usually within 6–12 months.

Processing & Timeline: The typical processing time is around 6–9 months from application to PR approval, although it can extend to about a year in some cases. Once the principal investment is made and all checks are cleared, the applicant is issued an Approval-in-Principle PR, and after fulfilling any last conditions, a final PR status is conferred. With PR, the individual enjoys the right to live and work in Singapore indefinitely (subject to 5-year re-entry permit renewals contingent on maintaining the investment or other criteria). Many HNWIs appreciate that Singapore PR is granted outright, rather than a temporary visa – it provides a stable status from the start.

Path to Citizenship: Singapore citizenship is possible for PRs, but it’s neither fast nor guaranteed. By law, a PR may apply for citizenship after two years of permanent residence. In practice, however, Singapore is very cautious in granting citizenship to new entrants. It often expects a longer period of residence (e.g. 5–10 years), strong integration (such as family ties, business footprint in Singapore, or even mandatory military service for second-generation males), and typically requires the individual to make Singapore their primary home. The processing of naturalization can take another 1–2 years and includes interviews. Importantly, Singapore strictly disallows dual citizenship for adults. Any applicant for Singaporean citizenship must renounce their previous citizenship as a condition of being granted the Singapore passport. This is a critical consideration for HNWIs – gaining the coveted Singapore passport means forfeiting other nationalities, which many may hesitate to do. As a result, most investor migrants simply retain PR status long-term (renewing it every 5 years) to avoid losing their original citizenship. Singapore PR already confers most practical benefits (right to live, tax resident status, etc.), so citizenship is often viewed as optional and pursued only if one is ready to embrace Singapore as a sole nationality.

Dual Citizenship: As noted, Singapore does not recognize dual nationality beyond age 21. Children born dual (e.g. one Singaporean parent, one foreign parent) must choose by age 22 which citizenship to keep. For an adult foreigner, acquiring Singapore citizenship necessitates renouncing other citizenships. The U.S. State Department explicitly warns that Singapore strictly enforces this policy and even mandates national service (military draft) for male citizens and PRs. Therefore, investor migrants need to carefully weigh this when considering naturalization. Many are content to remain PRs, which lets them keep their original passport while enjoying Singapore’s benefits. PRs can live freely in Singapore, and if privacy and security are the main goals, PR status is usually sufficient. In summary, dual citizenship is not allowed in Singapore (a notable contrast to other jurisdictions in this list), so attaining the Singapore passport comes with significant trade-offs.

Key Benefits: Singapore’s program appeals to those seeking a safe, world-class city with strong rule of law and financial privacy. No minimum physical stay is required to maintain PR (though for citizenship one would usually reside substantially). Singapore’s tax regime is very friendly to international wealth: no tax on foreign income (if not remitted), no capital gains or estate tax, and special schemes for new residents. Indeed, even as a citizen, one is only taxed on a territorial basis – meaning some new citizens pay no Singapore tax if their income is entirely offshore. This residency-by-investment route, while expensive and stringent, provides a pathway to an Asian financial powerhouse known for stability and confidentiality. Singapore combines the advantages of a major financial center (modern infrastructure, top banking services) with a tradition of privacy, making it a top choice for wealthy individuals from around the globe.

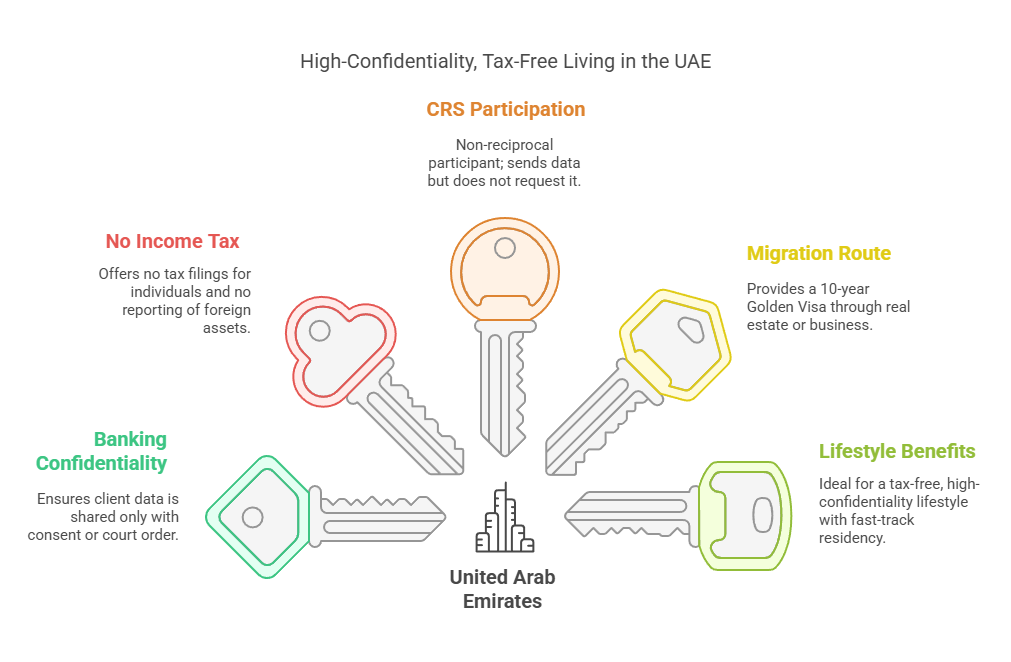

United Arab Emirates (UAE)

Banking Secrecy: The United Arab Emirates, particularly Dubai and Abu Dhabi, has emerged as a prominent haven for financial privacy. The UAE’s banking laws mandate strict customer confidentiality. Under Article 120 of the UAE Central Bank Law (Federal Law No. 14 of 2018), all customer data and information held by banks “should be considered confidential in nature”. Banks and financial institutions are legally obliged to protect client information and may not divulge account details to third parties without customer consent or a legal requirement. The UAE’s Central Bank Consumer Protection Regulation (2021) further reinforces that banks must treat consumers’ information as private and confidential, collecting only necessary data and obtaining express consent before sharing any personal data. In practice, UAE banks do not release client financial records to foreign authorities absent a formal legal process. Culturally, the UAE has valued business secrecy and personal privacy, aligning with its role as a safe haven for global capital. Many HNWIs have taken comfort in the fact that UAE banks historically did not readily cooperate with foreign tax probes, and even now cooperation is carefully controlled. The absence of public disclosure requirements (no public bank account registries, etc.) means one’s financial affairs in the UAE remain discreet.

Data Protection: The UAE recently enacted a comprehensive Personal Data Protection Law (PDPL) in 2021 (effective 2022) which establishes an EU GDPR-like framework for privacy. It grants individuals rights over their personal data and imposes duties on entities to secure and not misuse data. Importantly, the PDPL coexists with sectoral laws like the Central Bank’s regulations on banking and credit data confidentiality. The Central Bank’s consumer protection standards require banks to implement strong data management controls, secure processing systems, and to notify the Central Bank of any data breaches. Customer financial data (identities, transactions, etc.) must be stored securely in the UAE and can only be made available to the customer or regulators – any sharing with external parties requires consent or legal mandate. These laws mean that personal financial information is well-guarded within the UAE, and even within government, access is limited to those authorities that have a clear legal right. Overall, the UAE provides a robust legal framework for privacy, underpinned by severe penalties for unauthorized data disclosure. This has solidified its reputation as a confidentiality-friendly jurisdiction.

Financial Reporting Requirements: The UAE is particularly attractive to HNWIs because it imposes no personal income tax at all (except recently a limited corporate tax and VAT, but no tax on individual income or wealth). Consequently, there are no annual income tax returns or asset declarations for individuals. A resident of the UAE does not have to report any foreign bank accounts, investments, or income to the UAE authorities, since there is no income taxation on individuals. There is also no exchange control – funds can flow in and out freely without government reporting. The only routine reporting might be anti-money laundering related (banks might need to report large suspicious transactions to the UAE’s Financial Intelligence Unit, but that is confidential and not for tax purposes). In summary, the UAE government does not require HNW residents to divulge their financial holdings or business interests elsewhere, which is a key privacy advantage. Living in the UAE means one’s personal finances remain one’s own business; the state isn’t collecting data on worldwide income or enforcing any wealth disclosure. This low-regulation, low-tax environment significantly enhances financial secrecy for those who relocate to the UAE. Even things like local bank interest or investment gains are tax-free, so banks don’t issue tax statements to individuals or governments as they would in higher-tax countries. The lack of financial reporting obligations is a core reason entrepreneurs and wealthy investors flock to the UAE – it offers legal residency with zero local tax bureaucracy.

Tax Transparency (CRS & FATCA): Historically, the UAE was considered outside the early wave of CRS adopters, but it has since joined. The UAE signed the Multilateral Competent Authority Agreement and began CRS exchanges around 2018–2020, somewhat later than Europe/Asia but now in effect. UAE financial institutions registered and started collecting foreign account data; the UAE’s first automatic exchange occurred by 2020 for some partners and by 2021 it was fully exchanging information. Notably, the UAE is categorized as a “permanently non-reciprocal” jurisdiction under CRS – since it has no personal income tax system, it is not seeking information from other countries, but it provides information to partners on their taxpayers’ accounts in the UAE. For example, Gibraltar’s records show that the UAE began sending data in 2021. Likewise, the UAE signed a FATCA intergovernmental agreement with the U.S. to report U.S.-owned accounts. All major UAE banks now comply with FATCA and CRS reporting requirements. However, in practice, experts note that UAE’s implementation of CRS has been cautious. The UAE ensures that only the required information is sent, and only to countries that have the proper legal framework (mirroring the approach of Switzerland and Singapore). Some investors still perceive the UAE as a place where, despite CRS, enforcement might be less aggressive – although one should assume compliance is real. The UAE’s late adoption gave it a window to attract assets from those fleeing early CRS adopters, and many of those assets remain. Overall, while the UAE does partake in global transparency, it remains one of the more privacy-oriented CRS participants, with fewer disclosure leaks or zeal in enforcement. It is also worth noting that as a non-taxing country, the UAE itself has no incentive to probe residents’ finances or share data beyond what’s agreed – it joined CRS largely to avoid blacklisting by the OECD. There is no domestic tax authority monitoring individual wealth.

Restrictions on Information Sharing: The UAE has legal safeguards that limit foreign access to information. Any foreign request for bank info (outside of CRS/FATCA automatic channels) typically must come through official treaties and the UAE’s Ministry of Justice. The UAE has mutual legal assistance treaties for criminal matters, but even then, the request must relate to defined serious crimes. Simply being curious about someone’s UAE holdings is not sufficient grounds. Additionally, until recently the UAE did not sign many bilateral tax information agreements. It relied on double tax treaties which have exchange of information clauses but those are used sparingly. Culturally and legally, the Emirates have been reluctant to share customer data; they perceive the UAE’s attractiveness as partly built on being a neutral safe harbor for wealth. It’s telling that some prominent figures targeted by sanctions or political pressure have relocated assets to the UAE – indicating a trust that the UAE won’t readily hand over information. With the PDPL and banking laws, unauthorized sharing of data is illegal, and officials or bank officers could face penalties for improper disclosure. That said, the UAE is increasingly cooperating on global standards (to maintain its reputation and avoid sanctions). For example, in early 2023 the UAE was removed from the FATF “gray list” by tightening controls on money flows. It will share data in bona fide cases of terrorism financing, etc. But for an ordinary HNWI, the practical reality is that the UAE remains one of the most private jurisdictions. Absent a significant legal issue, their financial information will stay in the UAE. In sum, the UAE provides a legally-backed assurance of privacy: client consent or UAE legal orders are required for information release, and automatic exchanges are limited to tax details under CRS/FATCA (with partners who must reciprocate and protect the data).

Residency by Investment – Pathways: The UAE’s investment migration options have expanded in recent years, moving beyond the traditional short-term residence permits to more user-friendly long-term visas. Key pathways include:

Property Investment Residency: A foreign investor can obtain a residency visa by purchasing real estate in the UAE. Historically, an investment of at least AED 1 million (~USD $270,000) in property qualified for a 2-year renewable visa in Dubai. Recently, under the Golden Visa scheme reforms (effective October 2022), a property purchase of AED 2 million (≈ USD $545,000) or more now grants a 10-year Golden Residency. The property must be retained (and not mortgaged beyond a certain amount). This is a significant lowering of the threshold, making UAE property investment one of the most affordable routes for a long-term visa given the no-tax context.

Business/Investment Golden Visa: The UAE Golden Visa program allows a 10-year residence for investors who either invest in a company, an investment fund, or as entrepreneurs. The criteria include investing at least AED 2 million (~USD $545k) in a UAE company or fund, or being a 50% owner of a company paying AED 250k in annual taxes. In essence, an investor can deposit AED 2M in an approved fund or show capital of AED 2M in a UAE business to qualify for the long-term visa. These requirements were streamlined in 2022 to make the threshold uniformly AED 2M for most categories (down from earlier AED 5M–10M amounts).

Entrepreneur/Talent Visas: Aside from pure investment, the UAE grants Golden Visas to individuals with exceptional talents (scientists, professionals, executives) and entrepreneurs who found startups with a certain revenue or funding. However, those are merit-based rather than passive investment and thus beyond the scope of pure “investment migration.”

Processing Time: The process for a UAE Golden Visa is relatively quick. Once the qualifying investment is made (e.g., property purchase completed or funds deposited) and documentation submitted, approvals often come in 1–3 months. In some cases, investors can even apply for a 6-month temporary visa to complete the investment inside the UAE, then convert to the long-term visa. The Golden Visa does not require continuous presence; one can maintain it without frequent visits (the earlier rule that a residence visa cancelled if you stayed out 6+ months does not apply to Golden Visas). This is ideal for HNWIs wanting a “privacy bolt-hole” – they can secure the visa and only reside as needed.

Naturalization & Citizenship: Traditionally, the UAE very rarely granted citizenship to expatriates. Naturalization was possible after 30 years of residence (per the law for non-Arab foreigners) but in practice this was almost unheard of. In a groundbreaking move, the UAE amended its nationality law in 2021 to allow select foreigners (investors, professionals, people with special talents and their families) to be nominated for Emirati citizenship. Under this scheme, rulers and government officials can put forward candidates who meet criteria (such as exceptional talent or contribution) for citizenship approval. Importantly, the 2021 amendments also permit these new citizens to retain their original citizenship – a major departure from the prior ban on dual citizenship. This means an investor who, say, significantly contributes to the UAE (beyond just buying property – perhaps establishing major businesses or being a globally recognized figure) could be granted a UAE passport without renouncing their previous nationality. That said, this process is discretionary and not open via application; there is no defined timeline or guarantee to obtain citizenship, even with a Golden Visa. It’s best viewed as a privilege that the UAE may confer on a rare few (indeed, some high-profile individuals have since received Emirati citizenship under this policy). For the vast majority of investor migrants, the UAE is a residency haven, not a new passport. But the change in law signals the UAE’s willingness to eventually allow a form of dual citizenship in special cases.

Dual Citizenship: For those exceptional cases, the UAE now allows dual citizenship (since 2021) for the new citizens it naturalizes. Previously, dual citizenship was formally banned – anyone who somehow obtained another nationality could lose UAE citizenship. Now, the policy is nuanced: if you are granted citizenship by the UAE under the new amendment, you may keep your other passports. This is huge for HNWIs because it removes the earlier disincentive (losing one’s primary citizenship). However, because citizenship is not something one can simply apply for through investment, dual citizenship considerations are moot for most. As a resident, you keep your original citizenship anyway. Should you ever be offered UAE citizenship, the law explicitly permits retaining it (which aligns with the UAE’s interest in attracting talented people who wouldn’t come if they had to renounce their origins). In summary, dual citizenship in the UAE is now allowed on a limited, invitational basis – a positive development for global investors, but not an integral part of the routine investment migration process.

Benefits and Considerations: The UAE ticks many boxes for financial privacy seekers. It offers a cosmopolitan lifestyle with modern amenities, zero income taxes, and high confidentiality. Through relatively moderate investments (around $0.5 million), one can secure a 10-year residency that can be renewed indefinitely. There is no requirement to reside in the UAE to keep the visa (making it ideal as a plan B residency). With new laws, even the possibility (however remote) of citizenship is on the table, now with dual citizenship permission in such cases. The UAE’s banking sector is world-class, and opening accounts as a resident is straightforward – then you benefit from the aforementioned secrecy. On the flip side, global transparency means if you remain tax resident in another country, your UAE bank might still report your account to that home country via CRS. But many investors actually use the UAE as their primary tax home (moving their residency from high-tax jurisdictions) precisely to legally avoid CRS reporting back to a high-tax country. Since the UAE itself doesn’t tax or pry, once you’re based there, your financial life can be structured with a high degree of privacy.

St. Kitts and Nevis

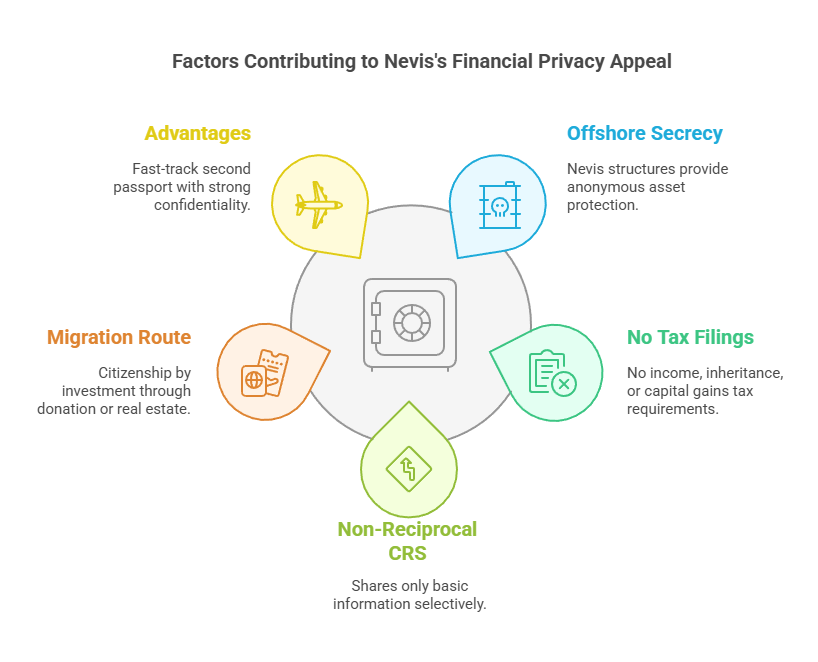

Banking Secrecy: St. Kitts and Nevis, a twin-island federation in the Caribbean, is famous for running the world’s oldest Citizenship by Investment (CBI) program (since 1984). Alongside its investment passport, it offers a quiet offshore financial environment. Nevis, the smaller island, in particular has a reputation as “one of the world’s most secretive offshore havens”. The country’s laws include strong confidentiality provisions. For example, Nevis has an Confidential Relationships Act that criminalizes unauthorized disclosure of information obtained in the course of financial business. Bank secrecy is deeply ingrained – financial institutions in St. Kitts & Nevis are not required to report client balances or transactions to any public registry, and traditionally, they did not readily share data even with foreign governments. A 2018 investigative report highlighted that, while many tax havens yielded to transparency pressure, Nevis “doubled down on secrecy” and kept its client information out of reach of foreign authorities. It noted that Nevis had been implicated in various international frauds precisely because its corporate and banking laws make it nearly impossible for outsiders to learn who owns assets there. Anonymous companies and trusts can be set up in Nevis with nominee directors, and Nevis does not maintain public beneficial ownership registers, nor does it recognize foreign court judgments seeking asset info without re-litigation locally. This all contributes to a robust financial veil. In short, banking secrecy in St. Kitts & Nevis is among the strongest in the Caribbean. While domestic regulators can supervise banks, the jurisdiction prides itself on protecting client confidentiality against outside inquiry, which is a selling point for its offshore services sector.

Data Protection: St. Kitts & Nevis does not have as elaborate personal data laws as, say, the EU or Singapore. However, it has taken steps under the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS) model to implement data privacy regulations. More pertinently, financial privacy is protected by specific statutes. There are legal oaths of secrecy required of financial industry workers. Also, Nevis offers renowned asset protection vehicles – Nevis LLCs and trusts – which by design keep financial data private (no public filings, and revealing information to foreign parties can be an offense). While a formal Data Protection Act is either nascent or in development, in practice the privacy of personal financial data is high. Additionally, as a small nation, St. Kitts and Nevis has fewer bureaucratic data-sharing systems; information largely stays where it is provided (e.g., within a bank or the citizenship unit) and is not disseminated. The government has shown commitment to confidentiality of CBI applicants as well – St. Kitts does not publish the names of new economic citizens. (Antigua is noted for explicitly not revealing CBI citizens’ names either). There was a case where a neighboring island (Grenada) saw a leak of a CBI citizen’s identity, which caused concern. St. Kitts & Nevis emphasizes that such breaches do not happen under its program.

Financial Reporting Requirements: For those residing or banking in St. Kitts & Nevis, the domestic reporting requirements are minimal. There is no personal income tax at all in St. Kitts & Nevis, and no capital gains or inheritance tax. Residents do not file income tax returns (there’s only social security and some local indirect taxes). As a result, individuals are never obliged to report their foreign incomes or assets to the government – because there is simply no tax basis to do so. This lack of reporting extends to companies under certain conditions: Nevis offshore companies (LLCs, IBCs) pay no local tax and file no public financial statements. The only time financial information might be submitted is if a company elects to use the domestic finance system, but even then it’s not publicly accessible. Additionally, St. Kitts & Nevis had a unique approach to financial disclosure for public officials (which doesn’t affect private investors) – in general, confidentiality is valued even in such matters. For an HNWI using St. Kitts & Nevis primarily as a citizenship option (and perhaps keeping assets via offshore structures there), an important point is that one need not live in the country to maintain citizenship or enjoy the tax benefits. If one did become a resident of St. Kitts & Nevis, they would find no local requirement to report worldwide wealth, aligning with the country’s status as a tax haven. This domestic opacity means any wealth an investor stores in St. Kitts & Nevis is not subject to local scrutiny or record beyond what the investor chooses to disclose.

Tax Transparency (CRS & FATCA): As part of international obligations, St. Kitts & Nevis has had to yield some ground. It signed a Model 1 FATCA agreement with the U.S. in 2015, so banks do report U.S. persons’ accounts to St. Kitts’ competent authority for transfer to the IRS. Under the OECD’s Common Reporting Standard, St. Kitts & Nevis committed relatively early (to avoid EU blacklisting) and made its first CRS exchanges by 2018–2019. It is listed as having provided information to partners from 2019 onward. However, St. Kitts & Nevis is classified as “permanently non-reciprocal” under CRS – meaning it provides data out but does not receive (since it has no personal income tax system). All major local banks and financial firms have put compliance systems in place, and now automatically exchange financial account info of non-citizen, non-resident clients to their home jurisdictions annually. This does somewhat diminish the anonymity for foreigners who park money in Nevisian banks and remain tax-resident elsewhere. That said, some sophisticated clients mitigate this by actually becoming a resident of St. Kitts & Nevis (or at least claiming tax residency there) so that their accounts aren’t reported to a high-tax country. Since St. Kitts & Nevis has no tax authority to receive info, a person who is solely a SKN tax resident in theory has their info collected by banks under CRS but no foreign partner to send it to (aside from perhaps sending it to SKN’s own competent authority, which would then just hold it). In summary, St. Kitts & Nevis has implemented CRS and FATCA on paper, but the practical impact can be managed by the savvy investor. Notably, Nevis in the past had very low participation in information exchange treaties, but under EU pressure, it has ramped up formal compliance. The jurisdiction still tries to differentiate itself by the fact that the information it does collect isn’t easily accessible or used beyond the strict scope of CRS requests, and it likely exchanges with far fewer countries than, say, an EU nation would.

Restrictions on Information Sharing: St. Kitts & Nevis has few treaties that compel wide-ranging information sharing. It has some Tax Information Exchange Agreements (TIEAs) with a handful of countries and mutual legal assistance treaties for criminal matters. But compared to larger states, its treaty network is limited. For a foreign government or creditor to get information, they often must obtain a local court order in St. Kitts or Nevis, which is not straightforward. Nevis in particular has built its offshore industry by creating legal hurdles for foreign inquiries – for instance, to pursue a Nevis trust, a foreign plaintiff must pay a substantial bond and litigate under Nevis law, and even then the trust laws severely restrict what can be divulged or seized. The banking law similarly won’t yield to foreign subpoenas unless a local court recognizes them. As the Guardian report noted, even UK investigators cannot get Nevis company ownership info (unlike in BVI where UK can access a registry). Secrecy pays, as Nevis’s officials openly acknowledge – it brings in registrations and fees. The government is thus incentivized to keep information sharing on a need-to-know basis. When CRS was being negotiated, these islands pushed for assurances that data wouldn’t be misused; if a partner doesn’t protect confidentiality, St. Kitts & Nevis can suspend cooperation. In effect, unless an investor is involved in serious crime that draws international enforcement, their financial details in St. Kitts & Nevis are very unlikely to reach prying eyes abroad. The main caveat is if their home country is part of CRS (which it likely is) and they haven’t changed tax residency – in that case a basic account balance would be reported. But aside from that automated process, no public or easily accessible private channels exist to inspect someone’s wealth in this federation. This includes the identities of CBI citizens – St. Kitts does not publish names of those who obtain citizenship by investment, so one’s new nationality can be kept quiet (only a few government officials know, under oath of secrecy).

Citizenship by Investment – Program Overview: St. Kitts & Nevis is often ranked among the top CBI programs for its longevity and benefits. It offers direct citizenship (passport) in exchange for an economic contribution, without any residency requirement. Investors have two main options:

Donation (Contribution) to a Government Fund: As of 2024, the minimum contribution is US$250,000 to the Sustainable Island State Contribution (SISC) fund for a single applicant. This is a one-time, non-refundable donation. (In previous years, St. Kitts ran limited-time discounts – e.g., $150k or $125k – but the government has standardized to $250k to align with other CBI programs.) The donation covers the main applicant; additional dependents require higher amounts (e.g. $300k for a family of four). St. Kitts is known to adjust its pricing – it recently reduced the contribution from $300k to $250k to stay competitive.

Real Estate Investment: An applicant may invest in approved real estate (such as luxury resort units or villas). The minimum investment was lowered in October 2024 to $325,000 (from $400k) for a share or condo unit, or $600,000 for a private single-family home. The property must be held for at least 5 years (previously 7 years at the lower amount). After the hold period, it can be sold, potentially even to another CBI seeker. This option usually incurs additional government fees ($25k+). St. Kitts’ recent changes made real estate more attractive by cutting the threshold to $325k.

Whichever route, applicants also pay due diligence fees (around $7,500 to $10,000 for the main applicant) and processing fees. There is also a smaller $10k government fee per additional dependent under the fund option.

Processing Time: St. Kitts & Nevis has historically prided itself on a swift process, roughly 4 to 6 months from application to passport. Under a premium accelerated process (for an extra fee), approvals have been issued in as little as 2–3 months. The timeline includes background due diligence by international firms. The government has an official 90-day accelerated application option. Generally, applicants can expect Citizenship certificates and passports in hand within half a year if all documents are in order. The efficiency and reliability of St. Kitts’ processing is a big draw – it’s a well-oiled machine after decades of experience.

Rights and Benefits: A St. Kitts & Nevis passport grants visa-free or visa-on-arrival access to about 150 countries, including the UK, EU Schengen Area, Hong Kong, Singapore, and others (not the US or Canada). It is valued for ease of travel and as a stable second citizenship. St. Kitts allows one to live in any CARICOM country as well. There is no requirement to ever reside in St. Kitts or even visit (though a brief visit is encouraged). There are also no taxes on worldwide income for citizens who choose to reside in the federation. Many CBI citizens don’t relocate; they use the passport for mobility and as a plan B. Some do use it to become tax resident in a zero-tax nation (by physically moving), thereby freeing themselves from their original country’s taxes and reporting – which ties back to financial privacy.

Dual Citizenship: Dual citizenship is fully permitted in St. Kitts & Nevis. The federation imposes no restrictions on multiple citizenship – in fact, it does not even ask applicants to renounce any allegiance. From independence in 1983, dual nationality has been allowed. The CIP’s success relies on this, as investors would not partake if they had to give up their original citizenship. As a result, when you obtain St. Kitts citizenship by investment, you retain your previous citizenship (assuming your home country also allows dual). The St. Kitts passport can simply be an addition. The government of St. Kitts & Nevis also does not inform other countries of your new citizenship. Thus, one can quietly hold this second passport for private use. Many HNWIs use their St. Kitts passport for banking or travel under a different identity, adding an extra layer of privacy. There is no obligation to disclose your other nationalities to St. Kitts, nor does St. Kitts share its citizens list with other nations. This policy of quietly allowing dual (or multiple) citizenship has been key to the CBI program’s appeal. In short, St. Kitts & Nevis recognizes and embraces dual citizenship as a matter of law and practice. You won’t lose St. Kitts citizenship if you acquire another, and vice versa.

Malta

Malta’s reputation as a secure financial hub stems from robust banking secrecy laws and stringent data protection standards, offering high-net-worth individuals a blend of financial privacy and favorable tax treatment.

Banking Secrecy and Financial Confidentiality: Maltese law imposes a strict duty of confidentiality on banks and financial institutions. The Banking Act and the Professional Secrecy Act require all officers to keep client information confidential at all times, even after their employment end. Unauthorised disclosure of banking information is a criminal offense punishable by fines and imprisonment. Banks may only release client data in specifically enumerated cases, such as when required by another Maltese law, upon a court order, with the customer’s direct consent, or in the investigation of serious crimes like money laundering. Outside of these exceptions, Maltese financial institutions rigorously safeguard client identities, account details, and transaction information. This legal banking secrecy framework – combined with a culture of compliance – ensures that private banking details are well-protected against unsolicited or foreign inquiries.

Data Protection: As an EU member, Malta adheres to GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) standards for personal data privacy. The national Data Protection Act 2018 implements GDPR locally, meaning banks and other firms must handle clients’ personal data under strict rules of consent, purpose limitation, and security. The Maltese Information and Data Protection Commissioner (IDPC) enforces these laws and can audit financial institutions to ensure compliance. In practice, this gives bank clients strong legal rights – including access to their data and the ability to correct or erase it – and requires banks to maintain robust cybersecurity and confidentiality protocols. Sensitive financial data in Malta cannot be shared or processed without a lawful basis, and violations can result in heavy penalties. These comprehensive data protection measures complement banking secrecy, creating multiple layers of privacy for account holders.

Financial Reporting Requirements: Malta’s tax system is attractive to foreign residents due to its remittance-basis taxation. Individuals who are resident but not domiciled in Malta are taxed only on income and capital gains arising in Malta, plus any foreign income remitted (brought into) Malta – foreign income kept abroad is not subject to Maltese tax. In other words, a Maltese resident non-dom is generally not required to declare worldwide assets or income as long as those earnings remain offshore. There are no wealth or net worth taxes in Malta, and no inheritance or gift tax on personal assets. This means Maltese residents do not file annual disclosures of overseas bank accounts or foreign-held wealth for local tax purposes (beyond reporting any income they actually remit to Malta). Domestic income (and any foreign income introduced into Malta) must be reported and is taxed at progressive rates up to 35%. However, the absence of wealth taxes and the remittance regime significantly reduces financial reporting obligations for those who keep its benefits in mind. High-net-worth residents often combine these rules with special programs (like the Global Residence Program) to enjoy a very tax-efficient and private financial life in Malta.

Tax Transparency Agreements (CRS and FATCA): Malta participates in global tax transparency initiatives despite its banking secrecy. Under the OECD Common Reporting Standard (CRS), Maltese financial institutions automatically exchange information on financial accounts held by non-residents with the account-holders’ home jurisdictions. Malta implemented CRS via the EU DAC2 directive in 2016, and as a result Maltese banks must annually report identifying details, account balances, interest earnings, etc., for clients who are tax-resident abroad. Likewise, Malta has a Model 1 FATCA intergovernmental agreement with the United States. Maltese banks identify accounts held by U.S. citizens or residents and send the data to Malta’s tax authority, which in turn provides it to the U.S. Internal Revenue Service. Through FATCA and CRS, Malta exchanges account information with over 100 countries. It’s important to note that these automatic exchanges occur within a legal framework – only the defined information is shared, and only with participating jurisdictions’ authorities. Maltese account holders who are solely Malta-resident (and not reportable elsewhere) are not subject to these disclosures. In summary, Malta complies with CRS and FATCA, meaning it does share financial data internationally, but this happens in a controlled, reciprocal manner rather than on an ad-hoc foreign request basis.

Restrictions on Information Sharing: Aside from formal automatic exchanges and EU obligations, Malta tightly controls any release of financial information to foreign governments. Bank secrecy will not be lifted at the mere request of a foreign authority or private litigant. Foreign governments or agencies seeking specific account details must pursue official channels – typically under a bilateral tax treaty, an EU administrative cooperation request, or a mutual legal assistance treaty for criminal matters. Even then, Maltese authorities will only provide information if the request meets the legal criteria (e.g. it’s for a defined serious investigation, with sufficient evidence, and not a “fishing expedition”). Maltese law enforcement or regulators can access bank records for their investigations and may cooperate with foreign counterparts, but such cooperation is governed by Maltese law and often requires a court order. In practice, this means foreign tax authorities can’t freely probe Maltese bank accounts unless the inquiry falls under an agreement like CRS or a treaty process that Malta has agreed to. This high threshold preserves financial confidentiality. Furthermore, Malta is party to the OECD multilateral convention on tax cooperation and numerous double taxation treaties, so it will exchange information when properly obligated – but always under the principle of specialty (using data only for the agreed purpose) and confidentiality. For investors, this adds reassurance that their financial affairs in Malta won’t be accessible to outsiders without due process and justification.

Investment Migration Pathways: Malta offers both citizenship-by-investment and residency-by-investment programs, attracting investors who seek EU residency, a strong passport, and financial privacy.

Citizenship by Investment (Naturalization for Exceptional Services) – Malta’s citizenship-by-investment program (officially the Maltese Exceptional Investor Naturalization) grants a Maltese passport in exchange for substantial economic contributions. Applicants must first make a non-refundable contribution to the National Development Fund on one of two tracks: approximately $750,000 (for an expedited 12-month residency route) or $600,000 (for the standard 36-month route). In addition, an investor must either purchase real estate valued at at least €700,000 (≈$770,000) or rent a property for 5 years with an annual lease of at least €16,000 (≈$18,000/year). They must also donate €10,000 (≈$11,000) to a Maltese non-profit or charity. When these requirements are fulfilled and a rigorous due diligence process is passed, the applicant and their family can be naturalized as Maltese citizens. The overall timeline is roughly 12–36 months of residency (depending on the contribution amount) plus about 6–8 months of processing for background checks and document approval. In the fastest case, an investor can obtain Maltese citizenship in just over 1.5 years. Malta’s citizenship-by-investment pathway is capped annually and applies the world’s strictest due diligence (vetting sources of funds, criminal history, etc.), ensuring only reputable applicants are approved. The end result is highly valuable EU citizenship, granting the right to live anywhere in the EU and visa-free travel to ~180 countries, achieved without sacrificing financial privacy in Malta during the process.

Permanent Residence by Investment (MPRP) – For those who prefer residence status, the Malta Permanent Residence Programme allows investors (and their families) to obtain indefinite Maltese residency in about 4–6 months without a citizenship requirement. The MPRP requires a combination of a government contribution and investment in real estate. Investors choosing to buy property must purchase Maltese real estate worth at least €300,000–€350,000 (depending on location) and pay a non-refundable government contribution of €28,000 (≈$30,000). Those opting to rent can lease a property for at least €10,000–€12,000 per year (5-year minimum contract) and pay a higher contribution of €58,000 (≈$62,000). In both cases, an additional administrative fee of €40,000 applies, and a €2,000 (~$2,200) donation to a Maltese charity is required. Once approved, the investor receives a permanent residence certificate and cards for the family, allowing them to live, work, and settle in Malta indefinitely. Notably, the MPRP has no minimum stay – one can maintain Maltese PR status remotely, which is ideal for privacy-conscious individuals. While permanent residency by itself does not grant an EU passport, it can put one on a path to ordinary naturalization after five years of actual residence. Many wealthy individuals use the MPRP to establish a foothold in Malta (and the EU) and enjoy benefits like visa-free Schengen travel, without immediate tax consequences. The program’s investment outlay (around $150,000–$170,000 total, excluding any property purchase which can be resold) is quite competitive for EU residency. Overall, Malta’s investment migration offerings are well-regulated and transparent, providing a balance of opportunity (EU access, tax advantages) and the country’s insistence on integrity (due diligence and compliance checks).

Naturalization Timelines: For investors utilizing Malta’s fast-track programs, the timeline to citizenship is short. Under the Exceptional Services investment route, an applicant can qualify for naturalization after 12 months of residency (if contributing the higher amount) or 36 months (with the lower contribution). This residency does not require full-time physical presence (investors typically satisfy it via periodic visits and holding a residency card), making the timeline quite attainable. After meeting the 12- or 36-month requirement and passing all due diligence, the citizenship certificate is issued within a few months – so the total time to a Maltese passport can be as little as ~1.5 years (in the 1-year option).

Outside the investment context, Malta’s standard naturalization process is lengthy and discretionary. By law, a foreign individual may apply for Maltese citizenship after five years of legal residence (five out of the last seven years, with one year continuous immediately before application). In practice, however, obtaining approval can take seven to ten years. Applicants must demonstrate deep ties to Malta – such as long-term residence, integration into society, and sometimes language knowledge – and the government has wide discretion to approve or reject cases. For example, one must usually have spent most of those five+ years actually living in Malta (not just holding a permit), and pass interviews about Maltese civics. Because of these strict criteria, the ordinary naturalization route is uncommon for purely economic migrants. Most high-net-worth individuals therefore opt for the investment routes or maintain residency status. In summary, naturalization in Malta via investment is swift (1–3 years) whereas the conventional route demands patience, genuine residence, and assimilation over many years.

Dual Citizenship Policy: Malta imposes no restrictions on dual citizenship. Both native-born and naturalized Maltese citizens are allowed to hold multiple nationalities. An investor who becomes Maltese can retain their original citizenship without issue – Malta’s Citizenship Act explicitly permits dual citizenship and will not require any renunciation. This liberal policy is a significant advantage, as it lets new citizens enjoy a Maltese/EU passport for travel and business while maintaining their home citizenship and financial ties abroad.

Panama

Panama’s modern skyline reflects its status as a global financial center. The country combines strict bank secrecy traditions with a territorial tax system, making it a popular jurisdiction for investors seeking financial privacy and residency in a low-tax environment.

Banking Secrecy and Financial Confidentiality: Panama has a long-standing culture of banking secrecy enshrined in law. By regulation, banks in Panama are prohibited from sharing client information with third parties except under very limited, legally defined circumstances. Specifically, Panamanian banks may only disclose details of a client’s accounts with the client’s consent or when required by Panamanian law via a competent authority. Article 111 of Panama’s Banking Law mandates strict confidentiality – bank officers must keep all information about clients’ transactions private, and breaches can lead to penalties. Clients in Panama have the right to privacy in their banking relationships by statute. Even within the bank, access to client data is tightly controlled, and banks are required to implement strong internal security systems to prevent leaks. The law carves out only narrow exceptions: for instance, a court order in a domestic criminal investigation, a request from the banking regulator for supervisory purposes, or disclosures needed under anti-money-laundering laws (e.g. reporting suspicious activities). Crucially, foreign governments cannot directly compel Panamanian banks to release information – any such request would have to be routed through Panamanian authorities and meet local legal standards. Panama’s unwavering commitment to confidentiality has historically made it very difficult for outside parties to penetrate banking records. Account holders benefit from a high degree of anonymity (accounts are often held through offshore companies or foundations) and confidence that their banks will not divulge information absent a serious legal reason sanctioned by Panamanian law. While Panama has strengthened transparency in recent years (in response to international pressure), its banks still operate under one of the world’s more protective secrecy regimes, contributing greatly to the country’s appeal in financial privacy rankings.

Data Protection: Panama introduced a comprehensive personal data protection law in 2019 (Law 81, effective March 2021) to bolster privacy rights in the digital age. Under this law, any entity handling personal data must obtain the individual’s consent and explain the purpose for data collection. Financial institutions, which manage sensitive personal and financial information, are obliged to keep such data confidential and secure in encrypted databases. The law grants individuals rights to access their data, correct inaccuracies, and even request deletion (analogous to “ARCO” rights found in GDPR regimes). Enforcement is overseen by Panama’s National Authority of Transparency and Access to Information (ANTAI), which can investigate complaints and impose fines for misuse of personal data. Notably, Panama’s banking sector has its own privacy regulations issued by the Superintendency of Banks, which in some respects supersede the general law. Banks were already bound by confidentiality duties (as discussed above), and in 2022 the banking regulator issued Rule 1-2022 to align banks’ data processing with the new law while maintaining industry-specific standards. In practice, this means Panamanian banks must implement rigorous cybersecurity measures, limit data access to authorized staff, and ensure client information isn’t misused or leaked. They are exempt from certain provisions of Law 81 only because they are subject to equally strict (if not stricter) sectoral rules. For the client, the end result is that personal and financial data in Panama enjoys strong legal protection. Banks cannot arbitrarily share or sell customer data, and any breach of confidentiality – whether via hacking or insider wrongdoing – would expose the bank to legal liability and regulatory sanctions. Overall, Panama’s data protection landscape is evolving to meet international standards, adding an extra layer of privacy on top of traditional bank secrecy.