Armenia has emerged as an attractive destination for foreign investors and entrepreneurs, offering a liberal investment climate and efficient business registration processes. As of 2025, Armenia consistently ranks among the top countries globally for ease of starting a business. Foreign investors considering market entry or expansion in Armenia typically face a strategic choice: buy an existing company or incorporate a new one. This comprehensive report compares the legal, financial, and operational implications of buying an existing business in Armenia versus starting a new company (incorporating). It draws on up-to-date Armenian laws, tax codes, and procedures to help international businesspeople, consultants, and legal professionals evaluate the optimal approach for their objectives.

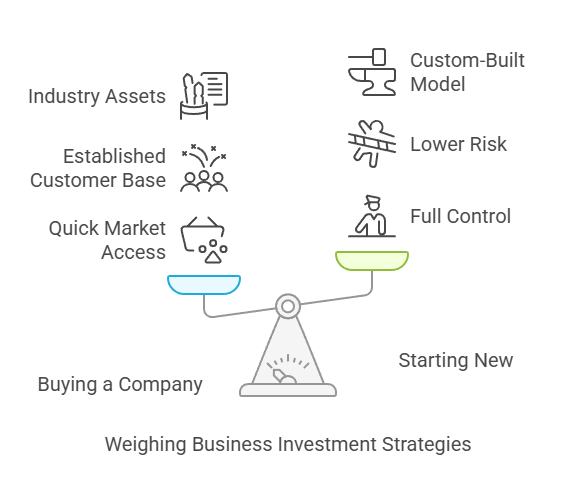

Both approaches have distinct advantages and challenges. Buying an established Armenian company can provide immediate market access, existing operations, and local goodwill – but it also carries risks like inherited liabilities and integration issues. Incorporating a new Armenian company offers a clean slate and full control, benefiting from Armenia’s quick and cost-effective company setup process, yet requires building the business from the ground up. In the sections below, we explore each option in depth, comparing legal frameworks, tax obligations, timelines, costs, and operational factors across common business structures (LLC, JSC, sole proprietorship). Whether you aim to buy a business in Armenia or start a company in Armenia, this guide will clarify the implications of each path in the Armenian context.

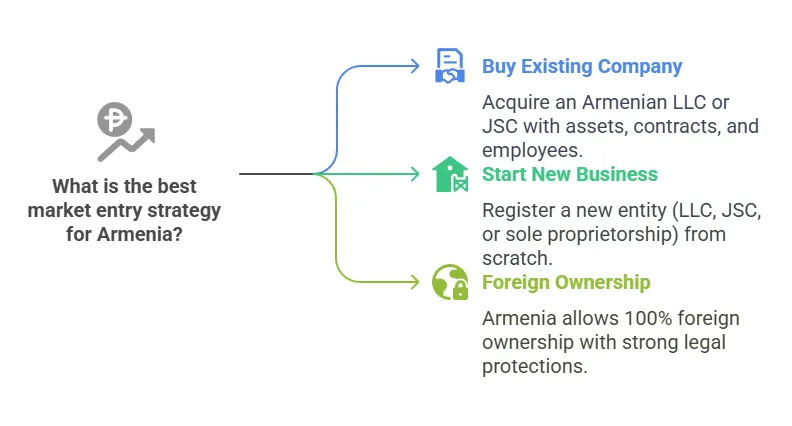

Market Entry Options in Armenia: Overview

Entering the Armenian market as a foreign investor can be done primarily in two ways:

Buying an Existing Armenian Company – acquiring an established business or its shares (a company acquisition in Armenia). This could involve purchasing a local LLC (Limited Liability Company) or JSC (Joint Stock Company), thereby obtaining its assets, contracts, and operations.

Incorporating a New Company in Armenia – registering a brand-new legal entity (such as an LLC, JSC, or as a sole entrepreneur) with the Armenian state authorities. Often referred to as Armenian company setup, this involves creating a business from scratch under Armenia’s company laws.

Both options are generally open to foreign investment in Armenia due to the country’s “open door” policy and national treatment of foreign investors. There are no broad restrictions on foreign ownership in most sectors, and 100% foreign shareholding is allowed in Armenian companies. Foreign investors enjoy strong legal protections: for example, if investment laws change within five years of an investment, the foreign investor can choose the more favorable previous law. Expropriation of foreign investments is prohibited except in extreme cases with fair compensation. These safeguards give confidence that either entry route – acquisition or new incorporation – will be on a level playing field with local businesses.

However, the choice between buying vs. starting anew involves different legal processes, financial commitments, and operational timelines. Below is a structured comparison to help evaluate which strategy aligns best with your business goals in Armenia.

Legal Implications and Regulatory Framework

Legal considerations are paramount when deciding between acquiring an existing company and incorporating a new one in Armenia. The laws governing company formation and transactions provide the framework for each approach:

Legal Framework for Incorporating a New Company in Armenia

Incorporating a new company in Armenia is a straightforward process governed by the Civil Code and specific laws like the Law “On Limited Liability Companies” and Law “On Joint Stock Companies.” Key legal points include:

Types of Legal Entities: Common structures are LLC (Limited Liability Company), JSC (Joint Stock Company) – which can be Open (OJSC) or Closed (CJSC) – and Sole Proprietorship (Individual Entrepreneur). LLCs are by far the most popular for small and medium businesses, including foreign-owned startups, due to flexibility and simplicity. JSCs are used for larger enterprises or when issuing shares (OJSCs can publicly trade shares, CJSCs cannot). Sole proprietorships are an option for a single-person business but do not provide limited liability protection. Partnerships and cooperatives also exist but are less common for foreign investors.

Founders and Ownership: Foreign individuals or companies can fully own an Armenian company (up to 100% ownership). There is no requirement for a local shareholder or director; even the sole director/CEO can be a foreign citizen not residing in Armenia. This means a foreign investor can incorporate a subsidiary or new company independently.

Minimum Capital Requirements: No mandatory minimum capital is required to register an LLC or CJSC in Armenia. Unlike some countries, you do not need to deposit initial share capital in a bank to establish the company. In practice, many LLCs start with a token charter capital (even as low as AMD 10,000) just for internal record.

Registration Procedure: Company registration is handled by the State Register of Legal Entities (Ministry of Justice). The process is highly efficient – it often takes as little as one business day to register a company, and at most 2–3 working days if documents are in order. Armenia even offers template charters and online registration (e-register.am) that can result in same-day registration for LLCs using standard forms. Required documents include an application form, the charter (if not using template), a founders’ decision/minutes, details of the company’s legal address and owners, and identification for founders and the director. Foreign founders must provide a passport copy authenticated by apostille or legalization and notarized translation into Armenian. Notably, no government approval is needed for foreign ownership – the law treats domestic and foreign founders the same in registration.

State Fees: Registration is free of charge for LLCs and JSCs. Armenia eliminated state fees to encourage new businesses. Sole proprietors pay a small fee (AMD 3,000, ~$8). The only costs are ancillary: e.g. translation and notarization of documents (around AMD 2,000 per page, ~$5), and optionally making a corporate seal (AMD 5,000–20,000, though seals are no longer mandatory). In short, incorporating a company has negligible official cost, especially by international standards.

Post-Registration: Once registered, the new company receives a state registration certificate and taxpayer identification. The company is a separate legal entity and can own property, enter contracts, and conduct business in its own name. Founders’ liability is limited to their capital contribution – personal assets are protected if the company faces debts or lawsuits. By contrast, a sole entrepreneur is legally inseparable from the owner – personal and business assets are one and the same, so the individual bears unlimited liability. After incorporation, certain businesses may need to obtain sector-specific licenses or permits before operating (e.g. financial institutions require Central Bank licensing in addition to registration). Companies must also file a declaration of their ultimate beneficial owners (UBOs) as part of anti-money-laundering compliance if a shareholder is another entity or if ownership changes.

Ongoing Legal Compliance: New companies in Armenia are subject to corporate law requirements such as holding an annual shareholder meeting and approving annual financial statements (within 6 months after year-end). LLCs and CJSCs have relatively simple governance (an annual meeting, and no board of directors required unless specified; JSCs with 50+ shareholders must have a board of at least 3). Armenian companies must maintain proper bookkeeping and submit regular tax reports; even small businesses are required to do monthly and annual accounting by law. Fortunately, reporting requirements are not onerous, especially under simplified tax regimes for small firms.

In summary, incorporating in Armenia is legally straightforward, inexpensive, and foreigner-friendly. It creates a new entity with no legacy baggage, under a stable legal system that protects foreign investors. The process mainly involves paperwork and compliance with basic company law formalities.

Legal Framework for Buying an Existing Company in Armenia

Buying an existing business – typically by purchasing its shares or assets – involves additional legal considerations compared to starting fresh. Key points to consider:

Transaction Structure: The most common way to acquire a company in Armenia is a share purchase – the foreign investor buys shares (equity) of an Armenian LLC or JSC from the current owner(s), gaining control of the company. In an LLC (which has “participants” rather than freely tradable shares), this means ceding the ownership interest; in a JSC, it means transferring stock. Less commonly, an acquisition can be done via an asset purchase (buying the business assets from the company) or a formal merger. Armenia’s Civil Code recognizes mergers, acquisitions, divisions, etc., as forms of reorganization where legal succession applies. In a merger scenario, one company is absorbed into another or two combine to form a new entity, with all rights and obligations transferred by law. Most foreign entrants, however, will opt for a straightforward share acquisition of an existing LLC or CJSC, because it maintains the target company intact (just with new owners).

Due Diligence and Agreements: Prior to purchasing, the investor should perform thorough due diligence on the target company’s legal, financial, and operational status. This includes reviewing corporate documents (charter, registration details), financial statements, tax filings, contracts, employee obligations, licenses, and any pending litigation or debts. It is common to use a due diligence questionnaire and request disclosures from the seller. If satisfied, the parties negotiate a Share Purchase Agreement (SPA) (or Merger/Acquisition Agreement) which sets the terms of the sale: price, payment, representations & warranties, indemnities for hidden liabilities, closing conditions, etc.

Regulatory Approvals: Generally, no government pre-approval is required to acquire a standard company in Armenia – foreign investors can freely buy shares in most sectors. Once the SPA is signed, the key legal step is to register the change of shareholders with the State Register. For LLCs, the new participant (owner) must be recorded in the state registry of legal entities. For JSCs, share transfers are often recorded via the company’s share registry (if privately held) or through the central depository (if it’s an OJSC with dematerialized shares). This registration is typically prompt (a few working days) once proper documents are filed, similar to a new company registration timeline.

Exception – Regulated Industries: If the target company operates in a licensed or strategic industry (e.g. banking, insurance, telecom, energy), a change in control might require approval from the relevant regulator. For example, acquiring a bank in Armenia needs Central Bank approval of the new shareholder. These are specialized scenarios; in most ordinary industry acquisitions (IT, manufacturing, trading companies, etc.), no special governmental consent is needed beyond standard registration.

Antitrust (Competition) Clearance: If the acquisition could affect market competition (typically if both the buyer and target have substantial market share in Armenia or the target is large), Armenian antitrust law may require notifying the State Commission for the Protection of Economic Competition. The law sets financial thresholds for mandatory merger control: if the combined assets or revenue of the parties exceed approximately AMD 4 billion (around $10 million), or if one party’s assets/revenue exceed AMD 3 billion, a notification and approval might be required. Foreign-to-foreign transactions that indirectly affect Armenian markets can also trigger this. In practice, many foreign investors entering Armenia by acquiring a local company will not hit these thresholds unless they are buying one of the larger companies in the market. It’s wise to check this and obtain clearance if necessary to avoid fines (up to 10% of income for not obtaining required approval).

Liabilities and Legal Succession: One critical legal implication of buying a company is that the entity’s liabilities travel with it. When you buy shares of an LLC/JSC, you inherit all the company’s existing obligations (debts, contracts, lawsuits, tax dues, etc.). Armenian law states that in reorganizations (merger/acquisition), all rights and obligations of the target transfer to the successor or acquiring company by law. In a share purchase (which is technically a change of ownership, not a reorg), the company remains the same legal person, so its liabilities remain in place – only the ownership has changed. This underscores the importance of warranties in the SPA and a careful due diligence to identify any “skeletons in the closet” (like undisclosed loans or legal disputes). Unlike starting a new company which has no prior history, an acquired business could have hidden risks.

Employment Law Considerations: If the company being acquired has employees, under Armenian law an ownership change does not automatically terminate or alter employment contracts – the employer is still the same legal entity. There is no legal requirement to notify or re-hire staff just because the shareholders changed. Employees continue their jobs under the existing terms. However, new owners often review key personnel and may eventually restructure staff or management. Armenian labor law would require certain notifications or severance if dismissing staff, but that’s an operational decision rather than a legal necessity from the acquisition itself. It is generally recommended to communicate with employees for morale, even if not legally mandated.

Transfer of Contracts and Permits: Since the legal entity remains the same in a share acquisition, usually its contracts with third parties (customers, suppliers, leases) and licenses remain in force. There is no need to re-sign contracts in the company’s name. However, savvy buyers check for change-of-control clauses in major contracts – some agreements might allow the counterparty to terminate or renegotiate if ownership changes. Similarly, certain government licenses (especially in mining or other concessions) might require notification of change in ownership. Ensuring continuity of business contracts and permits is a due diligence point.

Closing the Deal: The final step to legally close an acquisition in Armenia is updating the State Register to reflect new ownership (for LLCs or sole proprietorship conversions) or updating share registers for JSCs. The buyer will then typically obtain a new charter document listing them as the owner, and the company’s official extract will show the foreign investor as the current shareholder. This legal registration consummates the deal.

Business Structures: LLC vs JSC vs Sole Proprietorship in Comparison

Whether you acquire or incorporate, you will encounter Armenia’s common business structures. It’s important to understand how Limited Liability Companies (LLC), Joint Stock Companies (JSC), and Sole Proprietorships (SP) differ in legal and financial aspects, as this can influence your decision and post-deal structure.

Limited Liability Company (LLC): This is the most prevalent form for both new businesses and acquisitions in Armenia. An LLC is a private company where participants hold shares (usually proportional to their investment) but these are not freely tradable on a stock market. Key features: no minimum capital required, at least one founder (can be 100% foreign), and liability of owners is limited to their share contributions. LLC governance is simple – it can be managed by a director (CEO) without a board, and decisions are made by the general meeting of participants. An LLC must hold an annual meeting but this can be done remotely if needed. A foreign manager is permitted; if a foreign director will reside long-term in Armenia, they should obtain a residency permit, but there is no work permit requirement for foreigners beyond their visa/residency status. LLC ownership changes (transfer of participation) typically require either approval of other participants or as set by the charter; however, a participant can exit and demand payment for their share’s value under some conditions. For foreign investors, an LLC provides flexibility, full control with one shareholder if desired, and straightforward setup. It’s also the form often used if you were to buy an existing small/midsize business – most are LLCs.

Joint Stock Company (JSC): A JSC is a company whose capital is divided into shares. In Armenia, JSCs can be Open (OJSC) or Closed (CJSC). An OJSC can offer shares to the public and have unlimited shareholders; a CJSC is essentially a private JSC with a capped number of shareholders and restricted share transfer. Foreign investors might encounter JSCs if buying a larger firm or if they plan to list shares in the future. Key points: JSCs have limited liability for shareholders (like LLCs). Governance: a JSC with over 50 shareholders must have a Board of Directors (at least 3 members). Both LLCs and JSCs must prepare annual audited accounts if certain thresholds are exceeded (e.g. turnover over AMD 1 billion triggers audit and publication requirements for JSCs). In an OJSC, shares can be freely sold to third parties (hence can be listed on stock exchange), whereas in a CJSC, share transfers are typically subject to pre-emptive rights or shareholder approval. If you incorporate a new company intending to attract many investors or go public, a JSC might be appropriate. If you acquire an existing Armenian JSC, be mindful of securities regulations (if it was public, ensure compliance with any reporting or tender offer rules). Otherwise, for most foreign investors, an LLC or CJSC is sufficient and simpler.

Sole Proprietorship (Individual Entrepreneur): This is a one-person business with no separate legal entity. Any individual (including a foreigner) can register as an Individual Entrepreneur (IE) in Armenia with minimal paperwork. The advantage is extreme simplicity – just register with passport and pay a small fee, and you can do business under your own name or a trade name. However, the owner has unlimited personal liability for all business debts. There is no legal distinction between personal and business assets. This structure might be attractive for a solo consultant or a very small enterprise due to simplified accounting options (Armenia’s tax code offers special micro-business tax regimes for individual entrepreneurs, discussed later). But for a foreign investor committing significant capital, an IE is risky because personal assets (even abroad) could be pursued by creditors of the business. Also, you cannot “buy” a sole proprietorship from someone in the way you buy a company – since it’s tied to an individual, you’d typically only acquire their business assets/goodwill. Thus, sole proprietorship is usually only relevant if you yourself start a very small venture. Most serious investors will prefer a company (LLC/JSC) for liability protection and continuity.

Branch or Representative Office (FYI): Instead of incorporating a subsidiary company, a foreign company can establish a branch (filial) in Armenia. A branch is not a separate legal entity – it’s an extension of the foreign company, and the foreign parent is fully liable for branch activities. Branch registration in Armenia is required if a foreign company wants a formal presence (it involves registering the branch charter and appointing a local representative). Branches can conduct profit-making activities if allowed. A representative office is similar but usually limited to non-commercial liaison activities. While not the focus of this report, it’s worth noting as a third option for market entry. However, given that Armenia’s company incorporation is so easy and liability separation is valuable, many foreign businesses opt for a subsidiary LLC instead of a branch.

Which structure to choose? For new incorporations, foreign investors overwhelmingly choose LLCs for flexibility, unless there’s a compelling reason to form a JSC (such as preparing for outside investors or required by law for certain activities). For acquisitions, you will inherit whatever structure the target company has; many local businesses are LLCs or CJSCs, which is convenient. If you end up acquiring a sole proprietorship’s business, you might transition it into an LLC for better structure. The table below highlights some key differences:

| Structure | Legal Personality | Owner Liability | Min Capital | Ideal For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLC (ООО) | Separate legal entity (company) | Limited to investment | None (or token amount) | Most foreign subsidiaries, SMEs (simple setup, full control) |

| JSC (OJSC/CJSC) | Separate legal entity (company) | Limited to investment | None | Larger enterprises, companies needing share issuance or public trading |

| Sole Proprietor (IE) | Not separate – individual business | Unlimited personal liability | None (just registration fee) | Small one-person businesses, freelancers; not suitable for significant investment due to liability |

Understanding these structures ensures you know what you are getting into. For instance, if buying a business in Armenia, verify if it’s an LLC or CJSC (likely) and the implications thereof. If starting from scratch, the LLC will probably be your go-to unless advised otherwise.

Financial and Tax Considerations

A critical aspect of the buy vs. start decision is the financial and tax implications. Here we compare initial costs, ongoing taxation, and potential financial risks for acquiring an existing company versus incorporating a new one in Armenia.

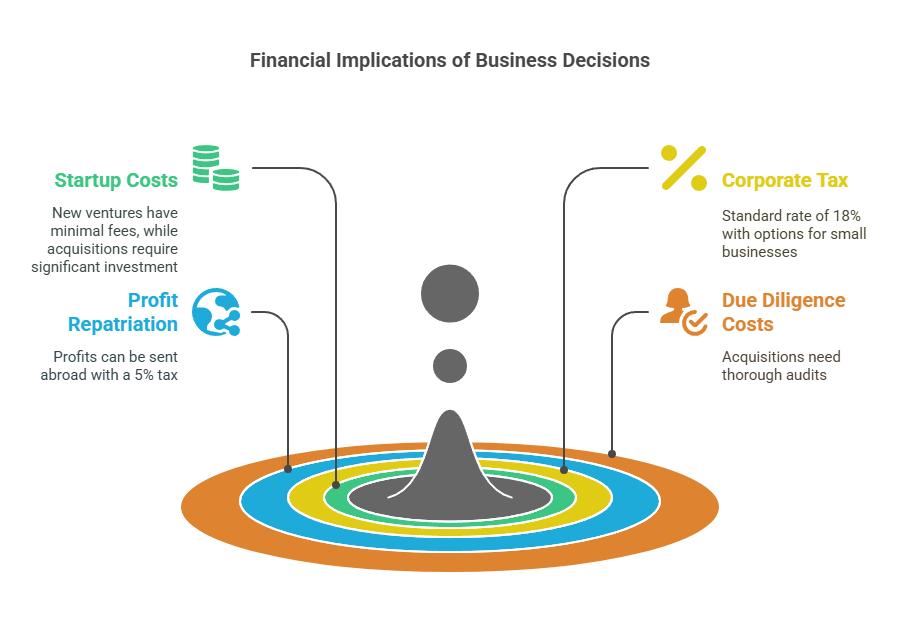

Initial Investment and Transaction Costs

Incorporating a New Company (Greenfield Investment): Setting up a new company in Armenia requires very little in terms of upfront fees to the government (as noted, registration is free for LLC/JSC). However, you will need to fund the new business’s operations – e.g. leasing premises, hiring employees, buying equipment – which can be considered your initial investment. There is no mandated minimum equity injection, so you have flexibility to capitalize the company as you see fit (some investors start with a small charter capital and later increase it once the business proves viable or needs expansion capital). If you hire local consultants or lawyers to handle incorporation and initial compliance, their fees will be part of your startup costs.

From a pure setup standpoint, Armenian company formation is cost-effective – minimal government fees and low professional service costs compared to many countries. Additionally, because you can start with a lean capital structure, your cash is preserved for business activities rather than locked as paid-in capital. This makes Armenia attractive for startups and new ventures.

Buying an Existing Company (Acquisition): The financial outlay here can be significantly larger and highly variable. Key components of cost include:

Purchase Price: This is negotiated with the seller and could range from a nominal amount (if you’re buying a defunct “shell” company just for its licenses or to save time) to millions of dollars for a profitable operating company. Essentially, you are paying for the established business’s assets, brand, and future income potential. The valuation might be based on earnings, assets, or strategic value. For example, a small local IT company might sell for a few hundred thousand dollars, whereas a company holding valuable real estate or a large customer base could be much more. This upfront price is the biggest cost difference – starting a new company doesn’t require paying someone for an existing book of business.

Due Diligence and Advisors: Foreign buyers should budget for legal, financial, and possibly technical due diligence. Engaging an Armenian law firm to review corporate records and an accounting firm to audit financials is prudent. These professional fees could be a few thousand dollars for a small deal or tens of thousands for a complex acquisition. It’s money well spent to avoid inheriting costly problems. There might also be costs for valuation consultants or industry experts if you need to assess the business’s market position.

Transaction Taxes/Fees: Armenia does not impose a specific transfer tax or stamp duty on share transfers at the national level. The registration of the share transfer with authorities is typically not expensive. If the transaction involves real estate, there may be some registration fees to update property records, but again these are not significant. In short, there is no heavy M&A transfer tax in Armenia; the deal cost is mostly whatever you pay the seller and your advisors.

Assumption of Liabilities: While not an immediate cash cost, note that if you buy a company with existing liabilities (e.g. an outstanding bank loan or tax debt), effectively the purchase price plus the liabilities is your total economic investment. Sometimes buyers negotiate to subtract debts from the price. You should factor in any needed working capital injections after acquisition – for instance, you might need to invest additional funds to pay off some of the company’s debt or to rejuvenate the business. This is different from a new incorporation where you typically start debt-free (unless you choose to borrow).

Taxation and Ongoing Financial Obligations

Armenia’s tax system in 2024/2025 offers a relatively favorable environment for businesses, with moderate tax rates and special regimes for small businesses. Whether you buy or start a company, understanding the tax implications is crucial:

Corporate Income Tax (CIT): The standard corporate profit tax rate in Armenia is 18% of taxable profits. This rate was reduced from 20% in recent years to attract investment, making it competitive in the region. A newly incorporated company and an acquired company face the same CIT rate on profits. Taxable profit is calculated on worldwide income for resident companies (which includes any Armenian entity you set up or acquire). Key point: if you buy an existing company, you inherit its tax profile – for example, if it has tax loss carry-forwards, those could potentially be used (Armenian tax law allows loss carry-forward for 5 years in many cases). Conversely, any pending tax audits or disputes transfer to you as the new owner. With a new company, you start with a clean tax slate (no prior obligations or losses).

Small Business Tax Regimes: Armenia has special tax regimes aimed at small and micro businesses, which can significantly reduce tax burdens if the company qualifies. These apply equally to new or existing companies, but an existing company might already be benefiting from one:

Micro-business regime: Businesses with very small annual revenue (up to roughly AMD 24 million, about $60,000) can qualify as micro-businesses and enjoy a 0% corporate tax rate. However, this regime excludes companies in Yerevan engaged in certain services/trade to prevent abuse by larger enterprises. It’s mostly for true micro-entrepreneurs (often individual entrepreneurs). If you start a tiny venture or buy one in a rural area, this could apply, but for most foreign investors aiming at larger scale, micro regime isn’t a long-term plan.

Turnover tax regime (small business): Businesses with annual sales up to AMD 115 million (≈ $290,000) can opt for a turnover tax of 10% on revenue instead of paying 18% on profit plus 20% VAT. This simplified tax replaces both VAT and CIT for eligible small businesses. Many local SMEs use this. If you acquire a company that’s on turnover tax, you may keep it there as long as it stays under the threshold and is in an allowed sector. If you start a new company, you can register for turnover tax at inception (must elect within 20 days of registration).

VAT (Value Added Tax): Standard VAT rate is 20% on goods and services. Companies must charge VAT once they are VAT payers and can reclaim VAT on inputs. VAT registration is required if annual turnover in the previous year exceeds AMD 115 million (the same threshold, roughly $300k). Below that, a business can choose voluntary VAT registration or stay non-VAT (for example under turnover tax). If you incorporate a new company and expect revenues over the threshold or want to be part of supply chains that need VAT invoices, you would register for VAT. If you buy a company, check its VAT status: acquiring one already VAT-registered means you’ll continue that and need to comply with monthly VAT filings. If it was under threshold and not registered, you might eventually have to register once growth pushes sales past AMD 115m. There is no VAT on the transfer of shares (share sales are usually VAT-exempt as a financial transaction), but an asset sale could have VAT implications if the seller is VAT-registered.

Personal Income Tax and Payroll: If you hire employees in a new company or take on employees in an acquired company, you’ll handle wage withholding. Armenia has a flat personal income tax of 20% on employee salaries as of 2025 (it was gradually reduced from higher rates in previous years). Additionally, employers must pay social security (pension) contributions, but those are relatively small flat amounts or percentages.

Repatriation of Profits: A key concern for foreign investors is the ability to take profits out. Armenia allows free repatriation of profits and capital – there are no currency controls restricting a company from paying dividends abroad to a foreign owner. However, dividends paid to foreign shareholders are subject to withholding tax (WHT). The standard dividend WHT for non-resident companies or individuals is 5% (for profits generated 2020 onwards). This is relatively low, and Armenia has double tax treaties that can reduce it further in some cases. For example, many treaties allow a 5% or even 0% rate if the foreign shareholder owns a substantial stake. The WHT on interest is 10% and on royalties 10%, but those typically concern cross-border payments if relevant. If you incorporate a new company, when it becomes profitable and pays you dividends, expect a 5% tax on the way out (which you might get credit for in your home country). If you buy a company, the same applies going forward. Any retained earnings the company had don’t get taxed again until distributed, but ensure prior years’ profits were taxed or exempt under some regime properly.

Inherited Tax Liabilities (for Acquisitions): When you buy an existing company, an important financial consideration is any tax liabilities or credits it brings. Armenia’s tax authority can audit past years; if the company had unpaid taxes, penalties, or was under audit, the new owner is responsible via the company. Conversely, the company might have tax overpayments or net operating losses to carry forward – which could be valuable. Part of due diligence is to review tax clearance certificates or audits. It might be wise to condition the purchase on no significant tax debts, or retain part of price in escrow to cover any that surface. Armenia’s tax administration is improving and focusing on compliance, so investors should ensure the acquired company was compliant. For a new company, you avoid historical tax issues but must build a compliance process going forward.

Accounting Standards: Armenian companies use either Armenian GAAP or IFRS (for public interest entities and some large firms). A new small LLC can keep books on a cash basis if under certain thresholds, especially if under the turnover tax regime. An acquired company might have established accounting systems; you might need to align them with your corporate standards. Fortunately, accounting expenses in Armenia (hiring accountants, etc.) are relatively low, and many outsource bookkeeping. You should budget for this as an ongoing cost in either case (monthly accounting/reporting is required). The complexity will increase if you have multiple employees (payroll reporting, etc.) or if you cross the VAT threshold (monthly VAT filings).

Financing and Capital Structure: One operational financial difference could be in financing options. An existing company with a track record might have easier access to local bank loans. Armenian banks might be more willing to lend to a company that has historical financial statements and assets, even under new ownership, than to a brand-new entity with no credit history. If you plan to finance the business partly through local loans, acquiring an established firm could give a head-start (though the bank may still require guarantees or a fresh credit evaluation). A new company will likely rely on the parent company’s funds or international financing initially, since local banks will treat it as a startup (unless you provide collateral or guarantees). Over time, however, a new company can build its credit.

Table: Financial Snapshot – Buying vs Starting

| Aspect | Buying Existing Company | Incorporating New Company |

|---|---|---|

| Upfront Cost | Purchase price (can be significant) + due diligence/legal fees; e.g. $100k+ for a small business (case-dependent) | Minimal (no state fees; maybe $1k in legal/admin fees); capital can be as low as needed to start operations |

| Assumed Liabilities | Inherit all company debts & obligations (must evaluate during deal) | None initially (start debt-free; any liabilities you take are new ones you incur) |

| Tax Regime at Start | Continues under current regime: could be 18% CIT or 10% turnover tax if qualified. Check compliance status. | Choose optimal regime upon registration (e.g. elect turnover tax if eligible); start with clean tax slate |

| Profitability | Immediate (if company is profitable, you have cash flow from day one) | Will likely take time to become profitable; need to fund initial phase from investor’s pocket |

| Working Capital | Company may have existing working capital, inventory, receivables. But might also need injection if undercapitalized. | Must fully fund working capital (bank account, initial expenses) – but you control how much and when. |

| Access to Credit | Possibly easier if company has credit history or collateral (can approach local banks with past financials) | New company has no history; likely relies on parent or must build credit over time before getting local loans |

| Tax Carryovers | May inherit tax loss carryforwards (benefit) or unpaid taxes (risk). Possibly existing tax ID and VAT status continue. | No carryforward or backlog – fresh tax ID. Can optimize from scratch (e.g. structure for VAT efficiently). |

| Incentives | If the business had special incentives (e.g. free economic zone benefits), buyer can often continue them if criteria still met. | Can apply for incentives if available. Might miss out on ones that required earlier establishment. |

Financially, the “buy vs build” choice boils down to paying a premium for an existing cash-generating operation versus spending gradually to grow a new venture. Tax-wise, Armenia doesn’t penalize acquisitions (no heavy transaction taxes) and offers equal opportunities for new and existing firms to benefit from low rates and treaties. The next sections will look at the operational timeline and practical considerations, followed by risk and case scenario analysis.

Operational Considerations: Speed, Integration, and Practicalities

Beyond legal and financial factors, operational implications are a major deciding factor. This includes how quickly one can start operating, the effort to integrate into the market, and ongoing management considerations.

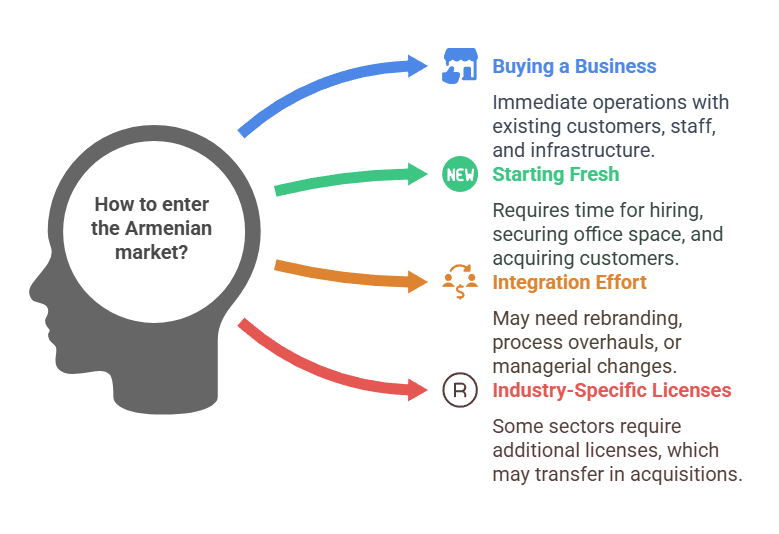

Timeline to Entry and Speed to Market

Perhaps the most significant operational difference is the timeframe to become fully operational:

Incorporating a New Company – Timeline: As noted, the registration itself is extremely fast (often within 1-3 days). So you can legally have a company ready to operate almost immediately. However, operational readiness involves more steps: opening a corporate bank account (which might take a few days to a couple of weeks depending on the bank’s KYC procedures – foreign-owned companies can open accounts but banks may require presence of the signatory to sign forms, etc.), finding office space or facilities, recruiting staff, obtaining any necessary business licenses (if your activity is regulated). For example, if you are starting a manufacturing unit, you’d incorporate, then lease a facility, register with tax authorities for VAT if needed, maybe get environmental permits, and hire employees – this could take a couple of months to truly start operations. If it’s a consulting or IT firm, you might be up and running in a matter of weeks since you mainly need the company, an office, and internet. In any case, the go-to-market timeline for a new venture is typically longer because you are building everything from scratch – product development, client acquisition, supplier relationships. Expect a ramp-up period where the company is operational on paper but still establishing itself in practice.

Buying an Existing Company – Timeline: The pre-acquisition phase can be time-consuming (sourcing a target, negotiating, due diligence). A straightforward small acquisition might close in 1-3 months; a larger deal could take 6-12 months. However, once the acquisition is completed, you have an immediate operational presence. The company you bought is likely already staffed, has an office or facility, and ongoing business activities. This means speed to market is much faster – you essentially skip the startup phase. For example, by buying a local distribution company, you overnight gain their contracts with suppliers and customers and can start generating revenue from day one of ownership. There might still be a transition period (for instance, integrating the company into your branding or adjusting processes), but in terms of market entry, acquisition is the fastest route. If timing is critical – say you need to service a big contract in Armenia next month – buying a company that’s already operational could be the only way to meet the deadline.

Ease of Setup vs. Integration Effort

Starting a new company means dealing with setup tasks but minimal legacy issues:

With a new company, you have the freedom to design all systems and culture as you wish. You can implement your own accounting software, internal controls, hire staff that fit your criteria, and launch a branding that aligns with your global identity. This “clean slate” is an advantage if you value a consistent corporate culture or proprietary processes. Operational control is total from day one – you’re not inheriting any unwanted practices. The flip side is you must create everything: internal policies, training new staff about your business ethos, establishing a client base from zero, etc. There is also a learning curve with local market practice – you might need time to understand local consumer behavior or B2B networks, which an existing company owner already had.

When buying an existing company, you skip the setup but face integration challenges. There will be existing processes and possibly a different corporate culture. For example, the company might have a certain way of managing inventory or a sales strategy that differs from what you would have implemented. As the new owner, you’ll need to decide what to change immediately versus what to keep to avoid disrupting operations. Employee integration is a key aspect: the staff will need to adjust to new leadership. Some may resist changes or fear for their jobs. It’s crucial to communicate your vision and possibly provide incentives for key employees to stay (to retain institutional knowledge and client relationships). Operationally, if the company used different IT systems or standards, you might incur time and cost to integrate those into your own. In an acquisition, post-merger integration is often cited as the hardest part – aligning the acquired business with your goals and ensuring synergies are realized. In Armenia’s context, this could include dealing with any language barriers, changing suppliers if you want to renegotiate terms, or rebranding the business under your global brand.

Another operational factor is location and infrastructure: A new company lets you choose your optimal location in Armenia (Yerevan is the business hub, but perhaps you want to set up in a free economic zone or a region to be closer to resources or benefit from lower costs). An existing company comes where it is – if it’s based in Gyumri and you prefer Yerevan, relocating the office or facility is an additional project. However, acquiring one in a prime location could save you the trouble of finding real estate in a tight market. For instance, if real estate or leases are hard to get in a particular industry (say, a mining site or a telecom license tied to infrastructure), buying the company that has them is the fastest way.

Continuity vs. Customization

Buying a company gives continuity – operations keep running as is, which can be beneficial for maintaining relationships. Clients and suppliers might experience no interruption if the transition is smooth (perhaps even unaware of ownership change if you keep the same company name and staff). This continuity can preserve value. With a new company, you have to build relationships from scratch. On the other hand, continuity means you also carry forward any inefficiencies until you address them. A fresh start allows complete customization of the business model.

For example, suppose you want to implement a new ERP system or a strict compliance program. In a new company, you set it up from the outset. In an acquired company, you may face resistance or have to retrain people used to the old ways. Likewise, a new company can be molded to target a specific market niche with laser focus, whereas an acquired company might have legacy lines of business you aren’t interested in (you can discontinue them, but it takes planning and might alienate some customers or employees).

Human Resources and Talent

Armenia has a talented workforce, especially in IT, engineering, and services. If your venture’s success relies on finding skilled labor quickly, an acquisition might give an immediate team. Acqui-hiring (acquisition for talent) is common in the tech sector – a foreign tech company might buy a local Armenian software firm primarily to gain its 50 experienced developers, which is faster than hiring 50 people on the job market. Retaining them is crucial; thus, as a new owner, you might offer retention bonuses or improved benefits.

Starting anew, you’ll have to recruit. The labor market in Armenia is such that good talent is available but may take time to attract, especially if you are new and not a known employer brand locally. You might have to rely on local recruitment agencies or networks. The advantage is you can hand-pick every team member. If cultural fit or specialized skills are important, you can curate your team. This process, however, can be time-consuming. The unemployment rate in Armenia isn’t very low, but skilled workers might already be employed, so enticing them to a brand-new venture (with no track record) could require paying a premium or selling them on your vision.

Also consider management bandwidth: a new operation in Armenia will need close attention from your side to establish; an acquired business might come with a local management team that you can either trust to continue running (if they are competent and you want a more hands-off ownership) or replace if needed. Many foreign investors keep the existing local manager for continuity, at least through a transition period.

Market Entry Strategy and Brand

From a marketing perspective, acquiring an existing brand can give immediate recognition. If the company you buy has a strong brand in Armenia, you inherit that goodwill – which can be crucial in sectors where trust and reputation matter. For instance, acquiring a well-known local food processing company means your products are already on store shelves and trusted by consumers. In contrast, a new entrant has to invest in marketing to build brand awareness from zero, which could take significant time and money.

On the other hand, if the existing brand has issues (say it suffered a recent PR problem or is seen as outdated), you might decide to rebrand after acquisition, effectively starting over in terms of brand building – in which case you paid for tangible assets and customer base more than the brand. If your strategy is to introduce a global brand into Armenia, starting fresh might align better (you use your international brand name from the start). Some foreign companies acquire a local player and then rebrand it to their global brand after a period. This can be a best-of-both: you get the operations but eventually have the unified brand. Just plan for the costs of rebranding (marketing campaign, new signage, etc.).

Flexibility and Risk Appetite

Operationally, starting a new company might be considered higher risk in terms of business success (since you have to win customers and prove the model in Armenia), but you have full flexibility to pivot or scale as you see fit. If the market conditions change, a small new business can adapt quickly without legacy constraints. Buying a company gives you a known quantity in terms of operations, but it might come with embedded risks (like dependency on a single big customer or an inefficient supply chain) that you’ll have to manage. It may be less flexible if it’s tied into long-term contracts or has ingrained ways of working.

One should also consider exit strategy: If things don’t go as planned and you decide to exit Armenia, which approach is easier to unwind? Selling an operating business that you built might be hard if it never took off (who will buy it?). Selling the company you acquired might be easier since it had value to begin with, although you would need to find a buyer willing to take it (perhaps the original owner might even buy it back in some cases). Alternatively, shutting down a new company you incorporated is relatively simple and low-cost (liquidation process in Armenia is not too complex but does require settling all liabilities and can take a few months). Closing an acquired business might be more painful if it had employees and assets (but essentially similar process of liquidation or you could resell the assets). So, operational exit is a slight consideration: a clean new entity can be closed or repurposed if plans change; an acquisition is a commitment to an existing operation that you’ll either turn around or eventually need to sell to someone else if you want out.

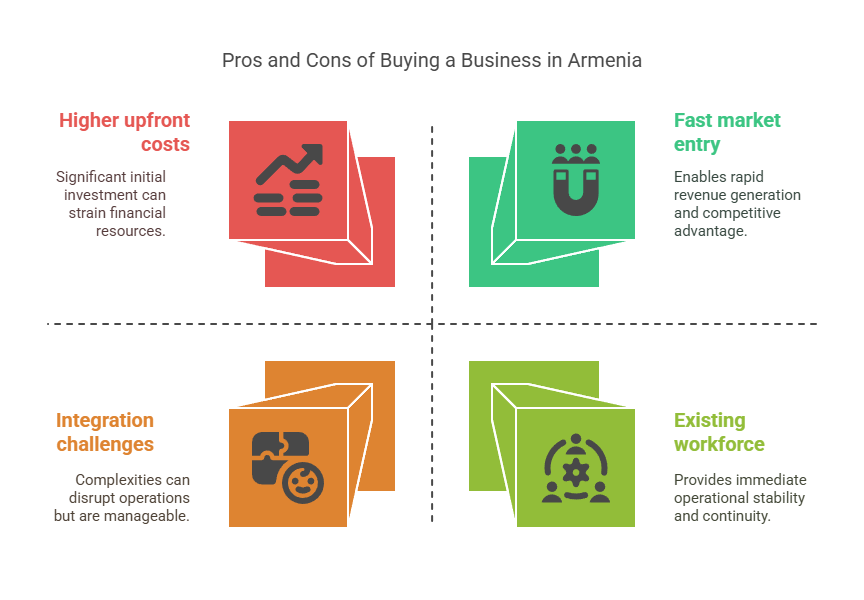

Risk Assessment: Pros and Cons of Each Approach

Both buying a business and starting a new one in Armenia come with their own set of risks and rewards. Below is a consolidated Pros and Cons comparison to highlight the critical factors:

Pros and Cons of Buying an Existing Company in Armenia

Pros:

Immediate Market Entry & Cash Flow: Instant access to established operations, existing customers, revenue streams, and ongoing contracts, enabling immediate cash flow and market presence. No waiting to build a customer base – you hit the ground running.

Established Local Relationships: The company likely has relationships with suppliers, clients, distributors, and perhaps government authorities, which can smooth navigation of local business culture. You benefit from the goodwill and networks the company built.

Trained Workforce in Place: A full team of trained employees is already on board, saving time in recruitment and training. This is especially valuable in industries where skilled labor is at a premium (e.g. IT, engineering) – you effectively buy a functioning team.

Known Performance History: You can review the company’s financial and operational history during due diligence, providing insight into expected performance. This reduces uncertainty about product-market fit or profitability compared to an untested startup.

Faster Expansion: If your goal is quick expansion, acquisition can be the fastest route. For example, buying a chain of stores instantly gives you distribution reach that would take years to build from scratch.

Cons:

Hidden Liabilities Risk: The biggest risk is inheriting problems – debts, legal disputes, tax underpayments, or environmental liabilities that weren’t obvious. Despite due diligence, some issues might surface only after takeover. These can cost money and time to resolve.

Integration Challenges: Merging the acquired company’s culture and processes with your own can be difficult. Resistance to new management, clashes in corporate culture, or IT integration issues can hamper realizing the full value of the acquisition. Poor integration can even lead to loss of key staff or customers.

Higher Upfront Cost: Acquisitions require significant capital outlay upfront to purchase the business (often far exceeding the cost of starting a new entity). This ties up capital and increases financial risk if the business underperforms post-acquisition.

Legacy Issues: The company might have outdated technology, inefficient processes, or unfavorable contracts that you are now stuck with (at least in the short term). Restructuring or renegotiating these can be costly. For example, the firm might be locked into a high-cost lease or a low-margin long-term contract.

Regulatory Compliance Catch-up: You may find the company wasn’t fully compliant with all regulations (labor, safety, etc.). As the new owner, you must fix these legacy compliance gaps. There could be reputational risk if the firm had a poor compliance record or negative public perception.

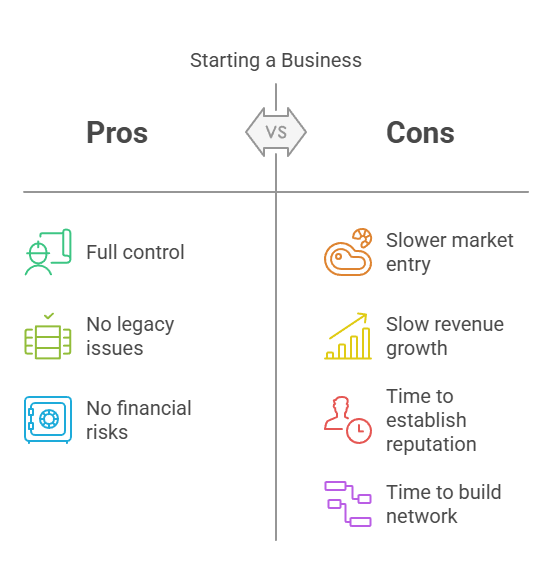

Pros and Cons of Incorporating a New Company in Armenia

Pros:

Clean Slate (No Legacy Issues): You start with a brand-new entity free of any past problems. No hidden debts or legal complications – full control to do things right from the beginning. This greatly simplifies risk management.

Low Cost and Easy Setup: Virtually zero cost to register and very quick process. You can allocate funds directly to business needs rather than paying a premium for existing operations. It’s financially more flexible, especially for entrepreneurs or small investors.

Full Control & Flexibility: You design the business model, choose the team, and set the company culture to align with your vision. Pivoting or changing strategy is easier because you’re not constrained by legacy commitments. This agility can be crucial in a dynamic market.

Optimized Structure: You can structure the company optimally from day one – for example, pick an LLC vs CJSC as it suits you, choose an ideal location, implement modern systems, and register for appropriate tax regimes (micro/turnover tax if eligible). Essentially, you build an “ideal” operation with the benefit of foresight.

Eligibility for Incentives: Sometimes new companies qualify for government incentives (like the IT startup tax benefits or grants for new investors). Being a new entrant might make you eligible for special programs targeting fresh investments.

Cons:

Slower Entry & No Initial Revenues: It takes time to establish operations and gain market traction. There is a period of zero or negative cash flow while you set up and develop the business. You must sustain the venture financially until it breaks even, which can take months or years.

Market Unknowns: As a newcomer, you may face a learning curve about the Armenian market – consumer preferences, regulatory nuances in practice, local competition. Mistakes or misjudgments can occur without an existing business’s experience to guide decisions.

Building Trust and Brand from Scratch: You don’t have an existing reputation; customers and partners might be hesitant to work with a new company with no track record. Establishing credibility can require extra marketing, networking, and possibly offering lower prices initially to win business.

Recruitment Challenges: Hiring a reliable team from scratch can be challenging, particularly for specialized roles. Without an existing local employer brand, attracting top talent might require time and offering above-market packages. There’s also risk in assembling a new team that hasn’t worked together before – it might take time to gel.

Opportunity Cost: If a market opportunity is time-sensitive (e.g., a sudden demand surge or a government project tender), starting from scratch might miss the window that an existing business could immediately exploit. Essentially, you might lose out to established players while you are still setting up.

To summarize: Buying a business in Armenia offers speed and established operations but comes with higher cost and integration risk. Starting a new Armenian company offers control and clarity but requires patience and heavy lifting to build the business. The best choice depends on the investor’s resources, risk tolerance, and strategic goals.

Timeline and Cost Comparison Table

To crystallize the differences, the table below provides a side-by-side comparison of timelines, procedural steps, and typical costs for buying an existing company vs incorporating a new one in Armenia:

| Factor | Buy Existing Company | Incorporate New Company |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Overall Timeline | 1–3 months (small deal) to 6+ months (large deal) to closing + immediate operations after closing. | 1–3 days for registration + additional weeks/months to set up operations (varies by business complexity). |

| Key Steps & Duration | 1. Find Target & Negotiate: Can take weeks or months. 2. Due Diligence: ~2–6 weeks for legal/financial review. 3. Contract Signing: SPA signing once due diligence is satisfactory. 4. Regulatory Approvals: If required (antitrust, etc.), add ~30 days. 5. Closing & Registration: Register share transfer with State Register (usually within 5 working days) – business now under new owner. 6. Post-Merger Integration: Ongoing (months) – align operations, possibly rebrand, etc., while business runs. | 1. Preparatory Work: Decide business structure (LLC, etc.), gather required documents (passport translations, etc.). 2. Registration Filing: Submit charter, forms to State Register – processed in 1-3 days (can be immediate with online templates). 3. Bank Account & Tax Registration: Open bank account (few days up to 2 weeks), notify tax authorities (often automatic with registration). 4. Initial Setup: Lease premises, obtain any licenses/permits (timeline depends on license type; many sectors unlicensed). 5. Hiring & Launch: Recruit staff, set up systems (could be parallel to above, overall a few weeks to a few months before fully operational). |

| Government Fees | – Company change registration: No significant fee (same free registration applies to changes in charter/ownership in most cases). – Notary fees: modest, perhaps AMD 20,000–50,000 ($40–$100) for document certifications if needed. – Regulatory filing fees: e.g. antitrust filing fee (if applicable) typically nominal. | – Registration fee: $0 for LLC/JSC incorporation (no state fee); sole proprietorship AMD 3,000 ($8). – Notary/translation: depends on founders docs, e.g. AMD 2,000 per page (~$5) for passport translation. – Company seal (optional): AMD 5,000–20,000 (up to $50). |

| Professional Fees | – Legal due diligence & transaction advisory: varies by deal size (e.g. $5k–$20k for mid-sized deal). – Business valuation or financial due diligence: optional, $5k+ depending on scope. – M&A broker fee: if using business brokers (often ~1-5% of deal value). | – Legal assistance for incorporation: optional (many do DIY). If hired, a local firm might charge $500–$1,500 for end-to-end setup service. – Accounting setup: minor initial cost, possibly part of service or $200–$500 for consultancy to register for taxes, etc. |

| Acquisition Cost / Capital | – Purchase price: Highly variable (from $10k for a defunct shell company to millions for operating business). This is the major cost in buying. – Assume liabilities: Must potentially allocate capital to pay off assumed debts, if any (e.g. cover $50k bank loan of acquired company). | – Initial capital injection: Up to the investors – could start with minimal (e.g. $1,000) and add funds as needed. No legal requirement to lock in capital. – Initial operating expenses: rent, salaries, equipment. E.g. budget $50k+ for first few months until revenue picks up (varies widely by business type). |

| Tax Registration & Status | – Continuity: Company likely already has a tax ID, VAT registration if applicable, etc. New owner should confirm any needed updates (e.g. change of CEO with tax authorities). – If on special tax regime (turnover tax, etc.), remains in place post-acquisition until criteria no longer met. | – Obtains tax ID upon registration (tax number issued as part of company registration). – Must separately apply for VAT number if needed (if expect to exceed AMD 115m turnover or choose voluntary VAT). – Can opt into turnover tax regime within 20 days of reg if eligible. |

| Licensing | – If the target business had required licenses (e.g. alcohol production, telecom), those licenses usually transfer with the company. However, check license conditions for change of control notifications. – No need to reapply; just ensure regulator is informed of ownership change if required. | – Must apply for any industry-specific licenses from scratch (timing depends on license – could be quick or several months). – Examples: to start a financial services company, you’d need Central Bank license after incorporation which adds time; for ordinary trading or IT, no special license needed, so no delay. |

| Commencement of Operations | – Immediately after closing: the company is already operating (staff working, services ongoing). New owner can observe or direct operations literally the next day. – Transition may involve meetings with employees and clients to announce new ownership, but business “keeps the lights on” throughout. | – Only after completing setup steps: e.g. after hiring key staff and putting infrastructure in place. If it’s a small consultancy, this could be just a week or two (you as owner start offering services). If a larger operation, might be 1-3 months to be truly up and running (factory built out, etc.). – There is an initial non-operational period which must be covered by investment capital. |

This table highlights that buying an existing company often front-loads costs and preparation (during the deal), but post-deal operations start instantly, whereas incorporating new front-loads minimal cost but requires a ramp-up period post-registration before operations yield results

Conclusion and Recommendations

Entering the Armenian market via company acquisition new incorporation each has its merits. Armenia’s pro-business regulations – from quick, free company registration to equal treatment of foreign investors – ensure that either path is feasible and relatively streamlined compared to many other jurisdictions. The decision ultimately hinges on the investor’s goals, resources, and the opportunities available:

Choose Buying an Existing Company in Armenia if your priority is speed to market, immediate scale, and leveraging existing local expertise. This route is ideal when acquiring a unique asset (such as a coveted license, prime real estate, or a dominant local brand) or a ready team that would be hard to assemble independently. It’s a fit for investors who have the capital to invest upfront and are prepared to perform due diligence and integration. Mitigating risks through thorough audits and good contracts (with representations and warranties) is essential. If executed well, an acquisition can provide a flying start in Armenia’s market and a quicker return on investment through ongoing operations.

Choose Starting a New Company (Incorporating) if your priority is control, gradual investment, and minimizing unforeseen liabilities. This approach suits those who have a clear vision for their venture and prefer to build it organically. It’s often favored for greenfield projects (like new factories or service centers) and when the available acquisition targets do not meet the investor’s criteria (e.g. outdated facilities or cultural mismatch). Armenia’s extremely business-friendly startup procedures – no minimum capital, no local partner required, online registration – significantly lower the barrier for foreign entrepreneurs to launch from scratch. With patience and sufficient working capital to sustain the initial phase, a new company can grow steadily and even outperform legacy businesses in efficiency.

In either case, foreign investors in Armenia should take into account the legal structure that best serves their strategy (with LLCs being the prevalent choice for flexibility), and ensure compliance with local laws and tax regulations. The tax environment is welcoming, with an 18% corporate tax and special regimes for smaller businesses. Profit repatriation is straightforward (5% withholding on dividends), allowing returns to flow back to the home country with minimal friction.

Recommendation: Conduct a market scan to see if a suitable acquisition target exists that meets your needs in terms of size, sector, and health. If one or more are identified, compare the cost of acquisition (and necessary improvements) against the projected cost and timeline of building an equivalent operation from scratch. If the premium for acquisition is reasonable and the target provides strong strategic value (like instant market share or technology), leaning towards “buy” may yield a better outcome. Conversely, if no appealing targets are for sale or if they come at exorbitant prices, it may be wiser to invest in your own new venture, taking advantage of Armenia’s supportive business setup ecosystem.

In conclusion, Armenia offers a fertile ground for both approaches. A foreign entrepreneur or investor can confidently start a company in Armenia within days, enjoying full ownership and a stable of incentives. Alternatively, one can acquire a company in Armenia and capitalize on existing foundations, backed by robust legal protections for investments. By carefully weighing the legal, financial, and operational implications outlined in this report, stakeholders can make an informed decision aligned with their market entry strategy and risk profile. Whichever path is chosen – buying a business in Armenia or starting a company in Armenia – the country’s growing economy and reform-oriented business climate stand ready to support the venture’s success.